Editorial: The Intimacy of Art

Hands, God’s hands — they hold the “cup of everlasting life,” the “reins of unconstrained power,” and, among other things, the keys to “the door of justice.” They ring the “Most Great Bell.” They mold the clay of human life. Hands are everywhere in the Bahá’í Writings, as is the mention of touch. Why? “Consider the sense of touch,” Bahá’u’lláh muses: “Witness how its power hath spread itself over the entire human body. Whereas the faculties of sight and hearing are each localized in a particular center, the sense of touch embraceth the whole human frame.” (Gleanings)

Surely this is true of ‘touch’ in both its literal and metaphorical meanings. Our hearts are ‘touched’ by art — by the pen that touches paper, by the paintbrush that touches the canvas, by the needle that touches fabric. And in the same way that physical touch affects the whole body, so does the metaphorical touching that is art have the capacity to permeate our whole being. What is the value of art if it does not offer such intimacy? Emily Dickinson spoke of recognizing genuine poetry by the feeling that the top of her head had been blown off; while I don’t experience poetry in quite that way, I can be so touched by it that it takes my breath away.

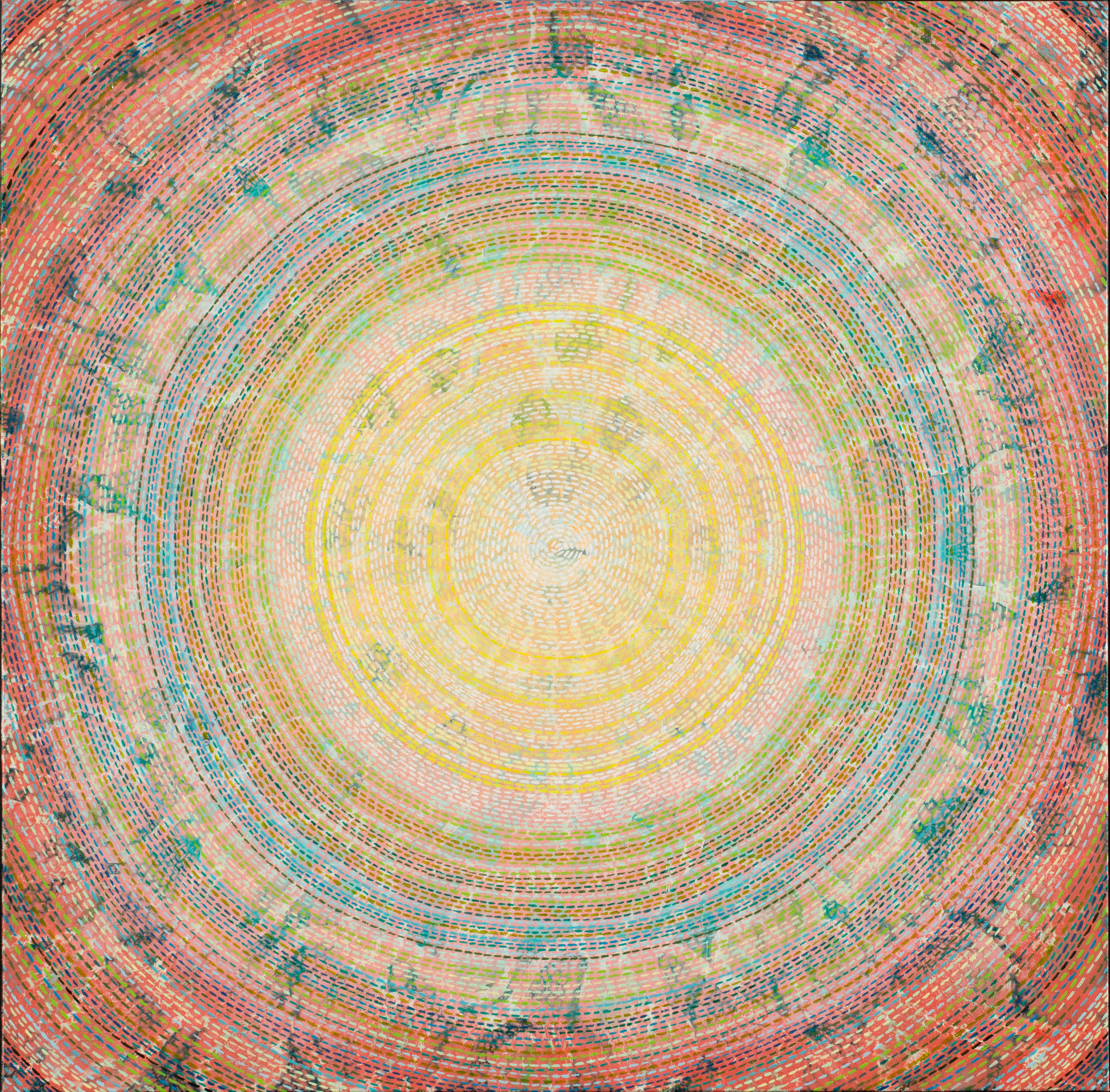

So it was when I encountered the work of visual artists Beth Yazhari and Nadema Agard: I had to catch my breath — here was pure poetry! “Arts, crafts, and sciences uplift the world of being, and are conducive to its exaltation,” Bahá’u’lláh writes. As I viewed Beth’s “Guardians of a Sacred Spot” and Nadema’s “Wampum Moon of Change,” I felt I was soaring in some empyrean of spirit. Beth’s work is work-ship, as are Nadema’s creations. Both artists invite us to soar with them in exalted spaces.

The work of reconfiguring, repurposing, reimagining has always been women’s work, and in the very tactile creations of these two women artists, such work reaches the level of worship. “Engage in crafts and professions,” Bahá’u’lláh enjoins us in the Hidden Words, “for therein lies the secret of wealth” — and what is being referred to here, I feel certain, is not just material wealth but also those spiritual treasures that are passed from one soul to another through the intimate medium of art.

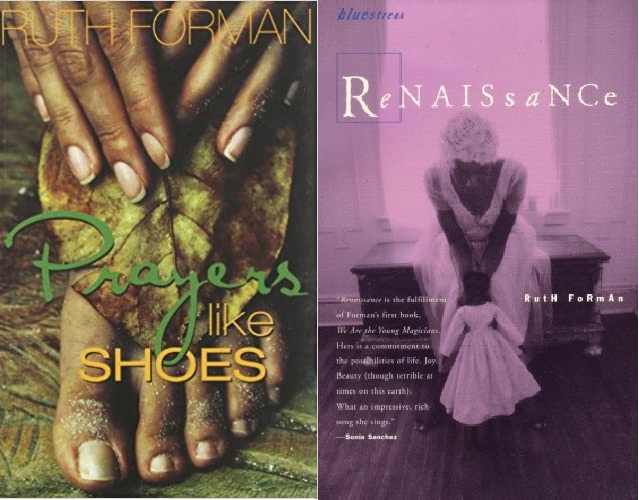

Poet Ruth Forman ‘goes to paper’ when her soul is stirred. In ‘I Go to Paper,’ Andréana Elise does not merely tell us about this accomplished poet, she calls forth her spirit. From Andréana’s rendering of a conversation with Ruth in a poem for two voices, we can glean much about where Ruth’s poems come from, what makes them work, and why they have the power to touch us.

We are delighted to present the work of Anthony A. Lee in our poetry section. In his poems, Lee ‘goes to paper’ to voice his hope for a better world, to set down what must not be forgotten, and to express his yearning for intimacy not only with the other but with the Beloved.

In my memoir-essay, “In the Noble, Sacred Place: One Rainy Day in a Holy City,” I tell the story of a life-changing encounter in the holy city of Jerusalem. I went to Jerusalem expecting to be moved by one spirit and found myself swept away by another.

We are pleased to feature an interview with Anne Gordon Perry, who spoke with me about writing for film. Rooted in the wisdom drawn from much experience, Anne’s answers to my questions give those who wish to write for film much to ponder.

This past month I was surprised to discover that in the far north of my state, the pine tree state of Maine, there lived a very literary soul who had translated the poems of Tahirih into Mandarin! In this issue, we share Zijing Pan DiCenzo’s translation of one of Tahirih’s best loved poems, “If I Should Gaze Upon Your Face,” next to the English translation by Shahin Mowzoon and myself, which appeared in issue # 7 of e*lix*ir.

The Personal Reflection Piece that appears in this issue explores a familiar Ridvan tablet. In “O Nightingales,” James Braun offers probing reflections on this tablet, rising to the heights of ecstasy as he meditates on that ecstatic moment when Bahá’u’lláh announced His Mission as the Promised One of all the ages.

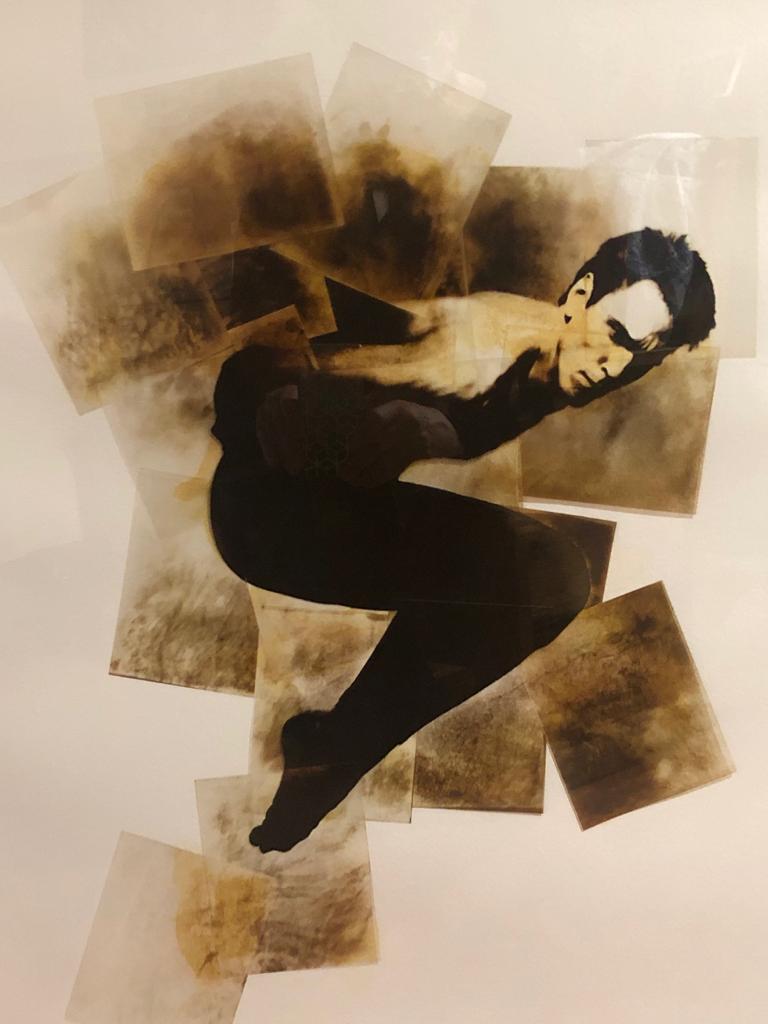

In this issue, we launch what will be a regular feature in e*lix*ir: the Artist Profile. Joyce Litoff joins our staff at e*lix*ir as a regular contributor whose mission it will be to introduce artists who, inspired by the Bahá’í vision and teachings, have a body of work behind them. In this issue, Joyce invites readers to enter the world of dancer Benjamin Hatcher. In Hatcher’s work, we see a lifetime of engagement with the body as “the throne of the inner temple,” as the Báb describes it.

In this latest installment of Ruhi & Riaz, Eira draws on oral history to give us the story of the ongoing persecution of the Bahá’ís of Ivel, a village in northern Iran that has been very much in the news this past while.

Hands are featured in both essays that appear in the “Voices of Iran” section of this issue. In “The Cherry Orchard” by Paria Bakshi, the hands that yearn to pick cherries are what save the author’s grandfather from certain death when he decides, one fateful afternoon, to take a different route home. In Melika Rezvani’s “A Wedding in Prison,” it is hands that beat pots and pans, and hands that arrange commissary cakes on a plate in a valiant effort to celebrate a wedding in prison. I doubt I have ever read a more moving — yes, touching — account of a wedding celebration, and I think you will feel the same.

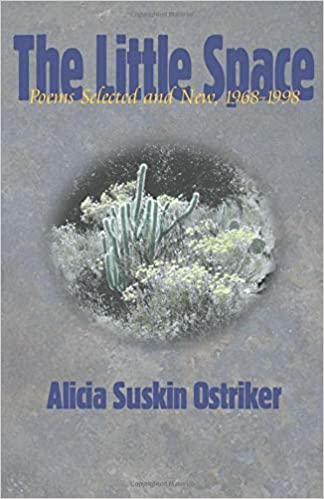

In “Looking Back on Books,” I offer some thoughts on the work of Alicia Ostriker, whom I met at an all-night Sufi poetry reading in the Galilee, and reflect on her quest as a Jewish woman poet to find a voice for her story.

It gives me special pleasure to feature, in the same section, the musings of our Assistant Editor, J. Michael Kafes, who, prompted by thoughts of the current commemorative year marking the centenary of the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, was drawn to reflect on his experience of creating a book about another landmark year, 1992, the holy year dedicated to the commemoration of the centenary of Bahá’u’lláh’s passing. In the Eyes of His Beloved Servants is a remarkable document that draws together the experiences of people from all around the globe who were touched by the radiant energies released by that remarkable year.

I will end by saying that before I sprained my baby finger last year, I could never have imagined how disabling it could be to lose the use of a single finger — and a baby finger at that! I had to see a hand therapist to get my finger working again. The way Jeannie cared for my hand instilled in me a new kind of respect for this remarkable appendage; and the work she did to rehabilitate my little finger changed the way I think about hands.

Now I understand that hands are not to be ignored, not to be taken for granted. They are what we must use to cling to the hem of the robe of the Beloved and to take the cup proffered by the Celestial Youth. Hands are made to be lifted up in praise and to “tear asunder the veil of vain imaginings.” And for those among us who are artists — writers, visual artists, musicians — the work of hands can give us passage into worlds of our own creation. Let me end by expressing a wish that is also a prayer: as you read this issue of e*lix*ir, may you be touched to the very depths of your soul by the intimate experience that is art.

— SLH