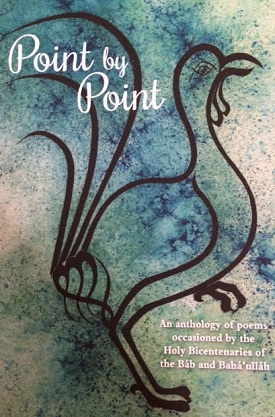

Point by Point

An Anthology of Poems...

Point by Point is what editor Anton Floyd describes in his foreword as a “flower gathering” and a “bouquet of poems that treat the perennial themes of the human spirit.” This anthology of work by 19 poets takes its title from a well known poem by Tahirih and offers the reader a wide range of poetic voices, all of which are, according to Floyd, “unified by their response to the spiritual impulse of the Bahá’í Revelation.” The result is 56 poems — some of which have been translated into Irish by Seosamh Watson — that, together, constitute what Floyd describes as “a poetry of devotion, commentary, and insight.” The attractive book cover features an evocative painting by Carole Anne Floyd entitled “Scented Ink after Mishkín-Qalam.”

Without doubt, the poems of this anthology do serve as a kind of “bouquet” of poetic expression, one that includes wildflowers as well as those breathtakingly beautiful roses that are the result of careful cultivation. Floyd has included the poems of celebrated nineteenth century Iranian poet Tahirih, as translated by Amin Banani; and of the renowned African-American poet Robert Hayden. In this gathering of flowers, we also have a number of contemporary poets with books behind them, foremost among them Michael Fitzgerald, a poet who has devoted a lifetime to the craft of poetry and produced many volumes of it. We also have the work of Mahvash Sabet, who recently achieved recognition from PEN Pinter International Writer of Courage Prize for Prison Poems, the stirring collection of poems she penned in response to her incarceration at the hands of the Iranian government.

Also featured in this volume is the work of e*lix*ir poets Sandra Lynn Hutchison (The Art of Nesting, GR Books, 2008); Valerie Senyk (I Want a Poem,Vocamus Press 2014); Lynn Ascrizzi, a well published Maine poet; and Youngin Doe, an accomplished poet and translator from Korea. Editor Anton Floyd himself recently published his first volume of poems, Falling Into Place (Revival Press, 2018); and although I have not seen this volume, a poem by Floyd included in this anthology , “Your Grandmother’s Garden,” testifies to his skill in evoking, in all their richness, the particulars of place. One moving poem by Sheila Banani caught my attention as I read through this anthology, as did the work of Imelda McGuire, an Irish poet with two volumes behind her, who is featured in this issue of e*lix*ir.

As for Floyd’s claim that the poetry in this anthology is one of devotion, commentary, and insight, devotional poetry has been written and written well for centuries, and when one writes in this genre, one has to be aware of the past, and be prepared to measure up to the standards set by it. As for insight, it is the task of the poet to look inside experience and see what others may not see. But the term “commentary” seems contrary to the very spirit of the poetic endeavor, and I would venture to say that the major flaw of some of these poems is their effort to do exactly this: to offer commentary on various subjects or themes, rather than rendering a deeply imagined experience that transforms the reader’s understanding of the subject. For without doubt, language is at the heart of the alchemy for which great poems are known. Without partaking of this elixir, the poet cannot make his or her poem into that rare and wondrous thing that finds its way into the hidden places of the heart.

While there are some genuine successes among the contemporary poems presented in this volume, one also finds a number of poems that appear to have sprung up from the soil of strong emotion or spiritual devotion or both. These flowers vary in their beauty and memorability. Some of these poets clearly need to wrestle longer and harder with language. In many cases, imagery could use an overhaul to achieve freshness. Some poems are rendered in conventional forms about which someone familiar with contemporary poetry might wonder. Innovation or unusual skill is required if a contemporary poet is to justify his or her use conventional forms and also engage the reader in such forms.

Why are the poems of the “greats” brought together with the work of contemporary poets whose enduring value cannot be known just yet and with the work of emerging poets who have far to go in the practice of their art? Clearly, Floyd’s anthology represents an effort to create a tradition, to bring together a group of writers who are united in their response to the Bahá’í revelation. But gathering work into this kind of bouquet inevitably invites comparisons and draws attention to the disparity between well loved poets who have earned their place in the tradition, established contemporary poets who have a certain mastery of their craft, and emerging poets who are only beginning to make their way. Nonetheless, plucked as they are from the garden of contemporary poetry wherever it grows up in the Bahá’í community, such volumes as Floyd offers the reader (and they are few and far between) represent a pioneering effort, and such efforts must be praised, for they are the first tentative explorations that move us, step by small step, towards the art that is destined to flourish in the golden age to come.

This volume truly is a bouquet of roses and wild flowers, some wilder in their beauty than others. Still we must praise, we must commend, we must admire Anton Floyd’s cultural activism in gathering together these poems and publishing this volume in honor of the Bicentenaries of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb. And Floyd’s cultural activism has not been limited to anthologies of poetry. This past summer, he saw that the poems of the e*lix*ir poets included here appeared along the Kilkenny Poetry Trail in West Cork. Yes, we must praise Anton Floyd for his pioneering effort and we cannot help but admire his passion for the difficult art of poetry, just as we must acknowledge the legitimate attempts of each of these poets to search for a voice to express their devotion. We must honor their efforts, and once we have done that, we must draw attention to a well established truth: genuine poetry does not simply flow from the heart through the pen (or the keyboard) to the world. Genuine poetry requires study, practice, and long apprenticeship. Let us go forth.

— SLH