As spring dawns in the northern hemisphere, bringing its first flowers and nourishing rains, the unnatural light emanating from exploding bombs brightens the skies over Ukraine. And as the Bahá’í community celebrates its Most Great Festival, those days on which Bahá’u’lláh declared His mission as the Prince of Peace, swiftly-passing fighter jets, like creatures of ill omen, cast furtive shadows over that land. One can almost imagine the fields of this richly agricultural country, the bread basket of Europe, crying out at being abandoned so close to sowing time, yet those who can, flee, seeking safe haven in neighboring countries. And the people of Ukraine are not alone in their suffering. According to the most recent report of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, active armed conflicts were taking place in at least thirty-nine states in 2020, with a total of 120,000 deaths issuing from these conflicts. As we ponder these numbers, we may wonder at humanity’s capacity for destruction. We may ask ourselves what it would take to eliminate war from the face of the earth? Is peace possible or is humanity destined to be forever plagued by the kind of conflicts we are now witnessing?

In these days of world-shaking crises, as some are wondering what our planet’s future will be and others if it has a future at all, we invite our readers to reflect on the words of the maiden who appeared to Bahá’u’lláh over a century ago in a garden just outside of Akka, Palestine. Presenting herself as “one of the Beauties of the Most Sublime Paradise, standing on a pillar of light,” she proclaimed herself to be the embodiment of the virtue of trustworthiness:

By God, the True One! I am Trustworthiness and the revelation thereof, and the beauty thereof . . . . I am the most great ornament of the people of Bahá, and the vesture of glory unto all who are in the kingdom of creation. I am the supreme instrument for the prosperity of the world, and the horizon of assurance unto all beings.

A symbol of the “Most Great Spirit,” the maiden is present throughout the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, but rarely do we meet her face to face. And in no other English-language tablet I know of do we meet her in a sacred garden — a “most sanctified,” a “most sublime,” a “blest, and most exalted Spot,” a garden whose symbolic significance is clear from the names Bahá’u’lláh conferred upon it — “Our Verdant Isle,” “Our New Jerusalem,” and “Our Green Island.”

“Our Green Island” — it is a designation we might well apply to our planet earth, which is, after all, only a small island of green in a sea of black space surging with waves of stars. Our fragile planet cries out for the kind of care the Ridvan Garden received from Abu’l Qasim, the loyal gardener Bahá’u’lláh appointed to tend it. It begs for the kind of attention shown it by the tender-hearted believers who carried flowering plants in their satchels, all the way from Persia, in the hope of beautifying the garden for their Beloved. Especially in the wake of the global crises that have appeared before us in recent months in all too predictable succession, our endangered planet demands of us the same kind of love the Manifestation of God showered on this small garden just outside of Akka.

Trustworthiness — as the words of the maiden make clear, this is no ordinary virtue, but a cardinal one upon whose cultivation so much, perhaps everything, depends. As we practice the virtue of trustworthiness in our most intimate relationships, we weave together the threads that will form the fabric of communities characterized by the same virtue. By striving to master this virtue, we engage in the divine art of building communities that are not merely safe, but vibrant and thriving — our own green islands.

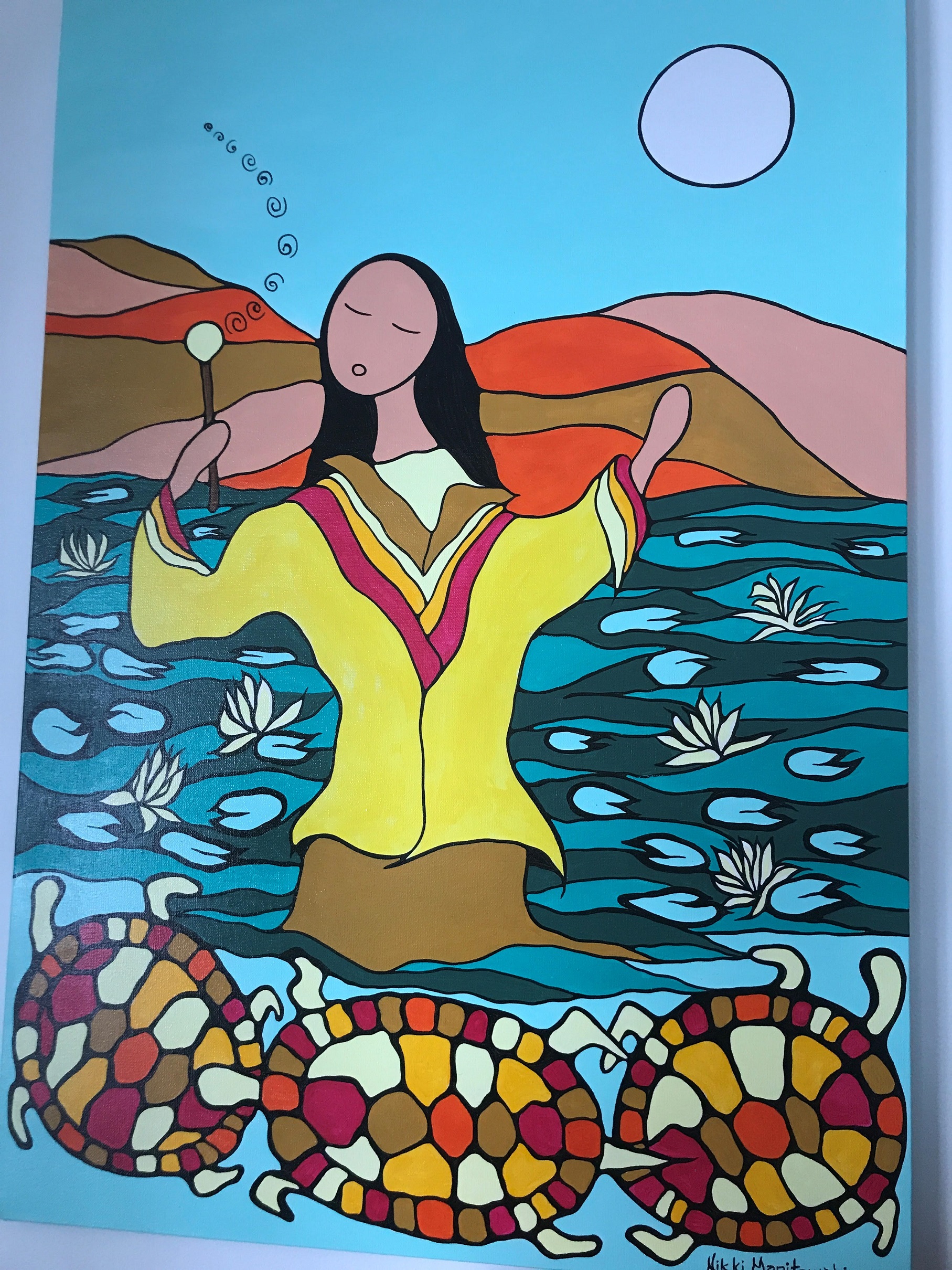

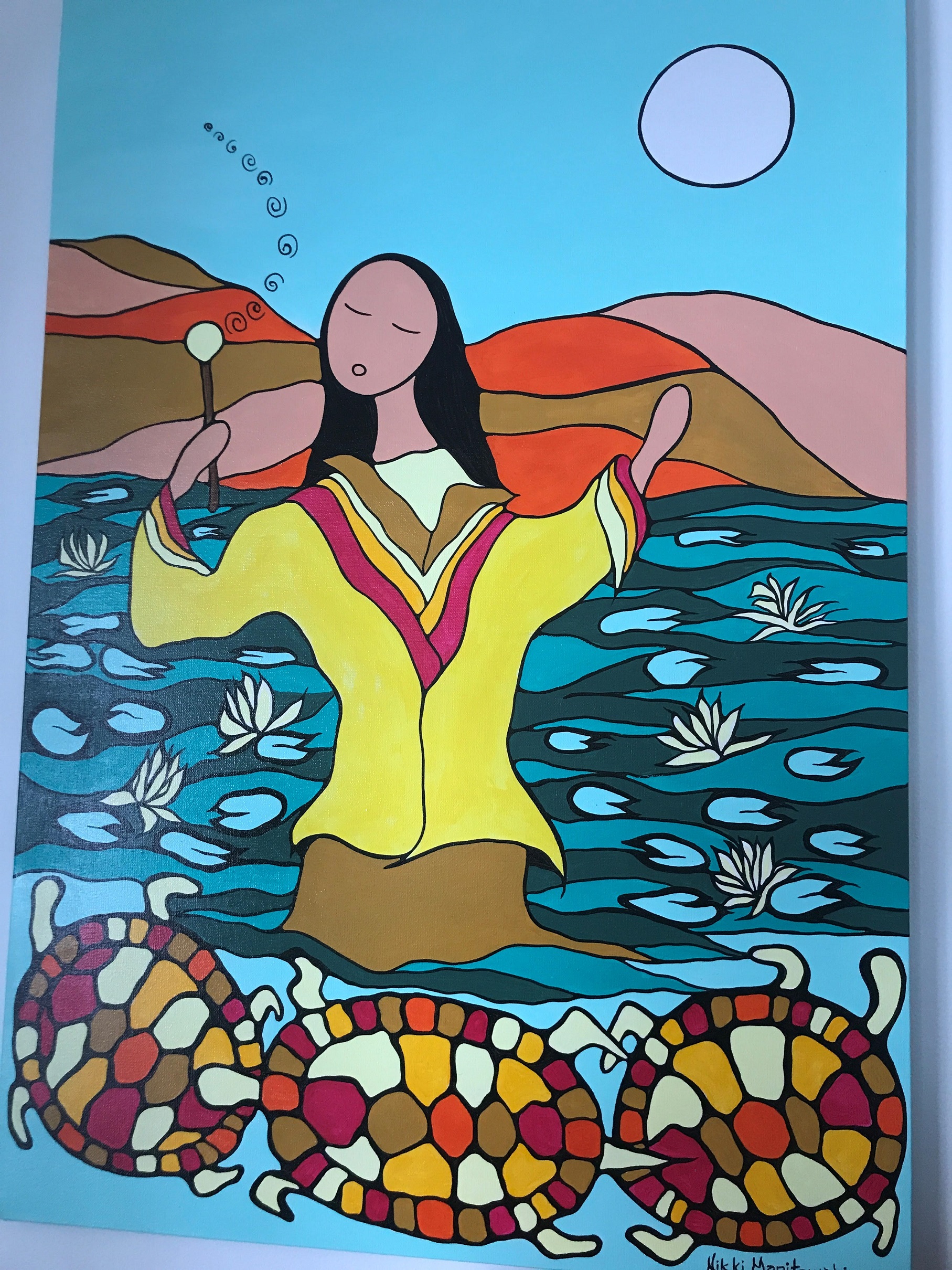

This issue of e*lix*ir is devoted to reflection on our “Green Island” and on the virtue of trustworthiness — its presence and its absence in our world. In the art section, we feature paintings by Pam Jackson and Nikki Manitowabi, both long-time residents of Manitoulin Island in northern Ontario, a place that is, quite literally, a green island for much of the year. Carried forward on the wings of prayer, their joint art project gives us a glimpse of life on an island that has, in recent times, become home to a community of white settlers, but which has long been home to a confederacy of Anishinaabe tribes — the Odawa, the Ojibway, and the Pottawatomi — and remains the site of the only unceded indigenous land in Canada.

Inspired by their reflection on Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of the maiden, Pam Jackson and Nikki Manitowabi sought to create a portrait of life on their green island and to evoke a vision of a community as it strives to embody the virtue of trustworthiness, in ways both large and small, not the least of which is a collaborative art project in which two painters from communities that have, for generations, been at odds with one another, come together to celebrate the gifts of their green island.

Two Personal Reflection Pieces appear in this issue. In “Our Verdant Isle: Finding Our Way Back to the Garden,” I reflect on Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of the maiden and ponder her potentially life-transforming words. I wanted to know: why is this virtue so important? What impact might its practice have on individuals and communities? Why did this virtue appear to Bahá’u’lláh in the form of a maiden? To find answers to my questions, I took to heart ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s guidance to “investigate and study the Holy Scriptures word by word.” (Promulgation of Universal Peace)

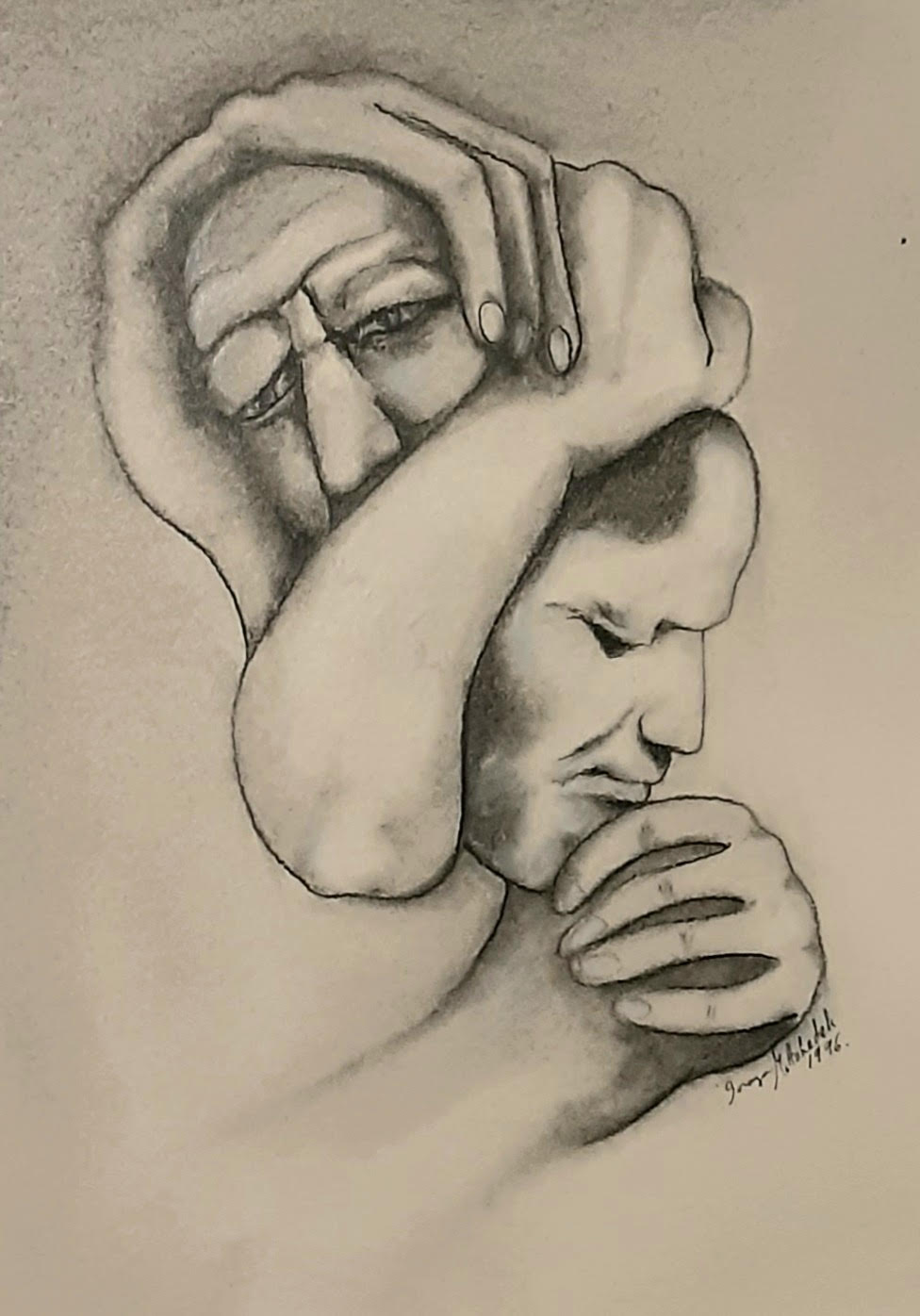

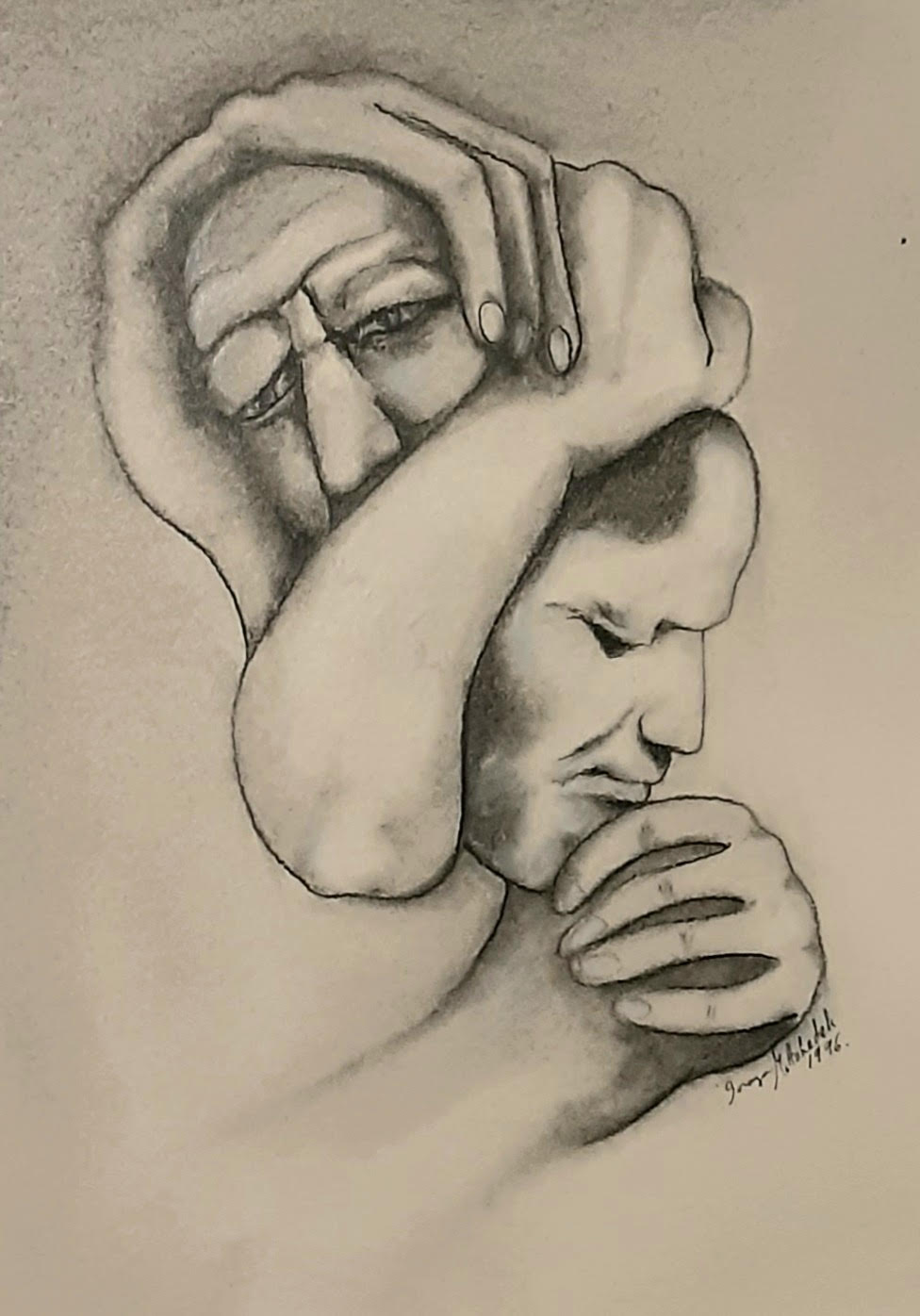

In “The Circle of Existence,” Susan Mottahedeh reflects on the twofold station of every human being, “one luminous, the other dark,” as elucidated in a tablet that appears in Light of the World, a selection of some recently-translated Writings by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá published to mark the centenary of His passing. The powerfully evocative sketch that accompanies Mottahedeh’s piece is the work of Canadian artist Soraya Tohidi.

In bidding farewell to this special year of reflection on the life and ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, a Personage who so perfectly embodied the virtue of trustworthiness in all His actions, we share some of the poems read at the Global Poetry Reading this past November to mark the centenary of His passing. In our poetry section, we offer poems by James Andrews, Harriet Fishman, Anthony B. Lee, Imelda Maguire, and Valerie Senyk.

We are delighted to feature Tami Haaland in our Artist’s Profile. A longtime Bahá’í, this former poet laureate of Montana is the author of three collections of poetry that have deep roots in the wild prairie landscapes and close-knit communities of rural Montana, yet strive to reach the worlds beyond this world. We are pleased to feature for our readers a handful of Haaland’s poems, both on the page and in audio recordings. In the profile, we also include the transcript of my interview with Haaland this past winter, an interview in which she reflects on her own journey as a poet and offers insights into the writing process, the purpose of poetry, and the place of the poet in the community.

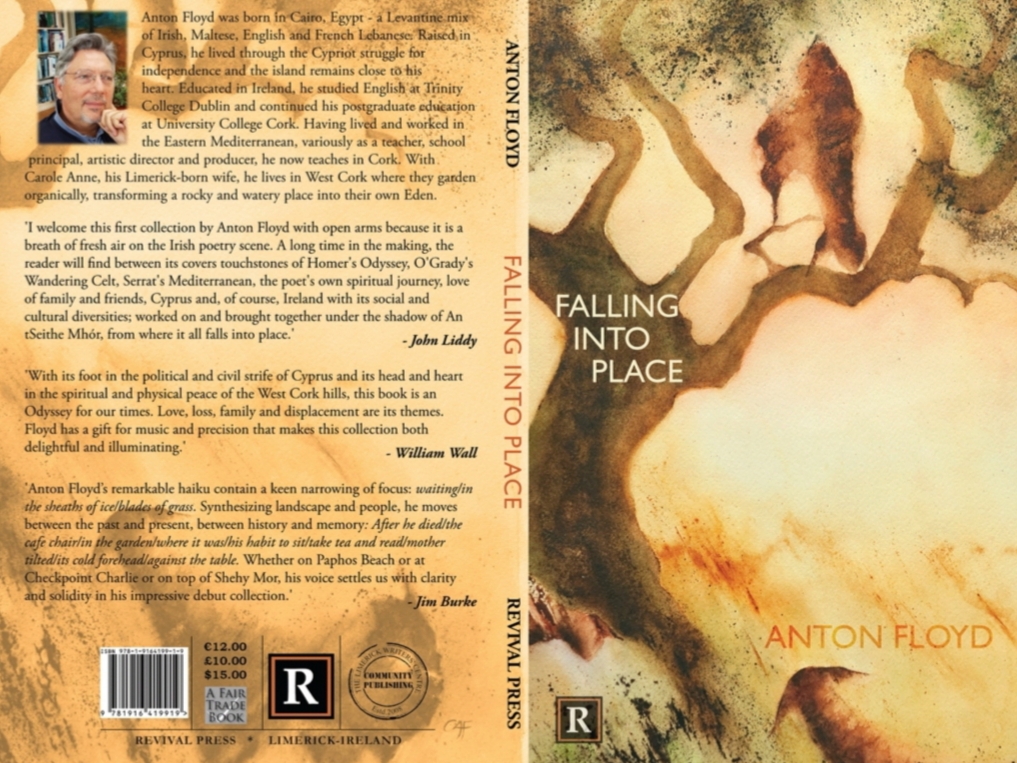

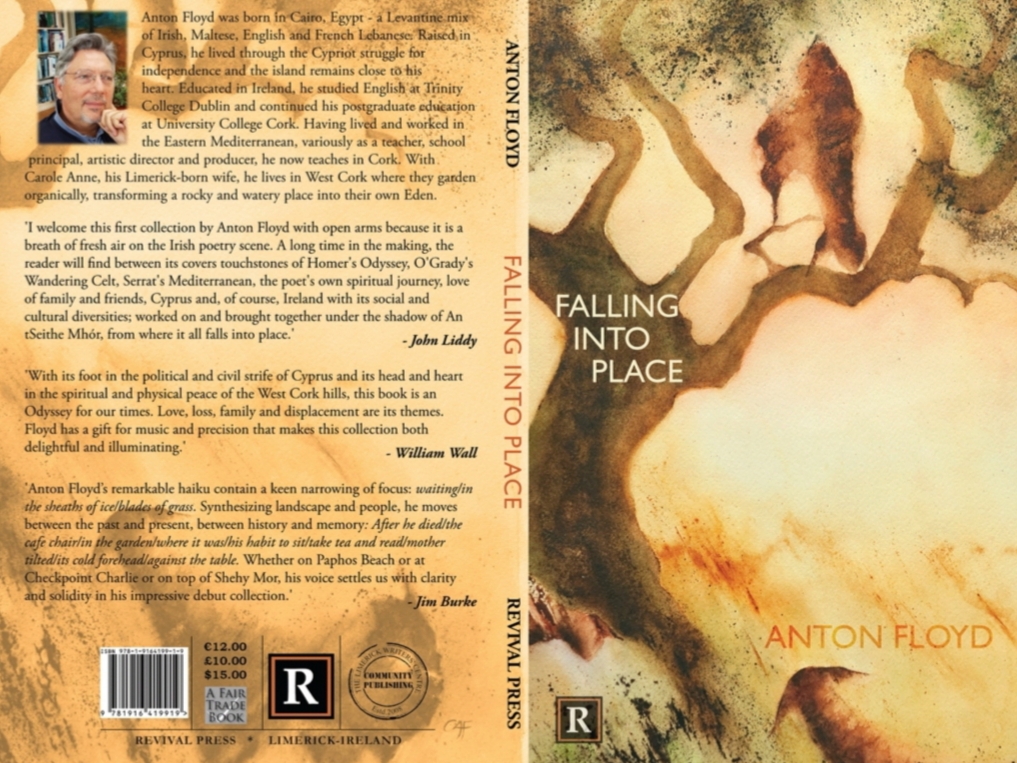

In “The Writing Life” column, we offer the reflections of Irish poet Anton Floyd on one of the most pressing issues of our time: forced migration and displacement. In “Giving Voice to Dispossession,” Floyd explains how a childhood ruptured by the Turkish invasion of Cyprus gave rise to his most recent book of poems, Depositions (2022). In our review section, Jim Burke offers his thoughts on Depositions and on Floyd’s 2018 volume of poems, Falling Into Place.

The fruit of meticulous and wide-ranging research, Richard Hollinger’s essay, “The Literary Life of Rosey Poole: Champion of the Oppressed,” offers a fascinating look at a remarkable but little-known life: the life of Rosey Poole, the first person to translate Anne Frank’s diary from Dutch into English, and an activist who, in the final years of her life, found in the Bahá’í teachings a way to express her life-long commitment to a multitude of social and literary causes, from the Black Arts’ Movement to the movement to dismantle apartheid. In his essay, Hollinger gives us an overview of the life of this social justice champion, a woman who found herself entrusted with the most widely-read holocaust diary to emerge after World War II and who took it upon herself to promote the work of African-American poets whose voices might otherwise have gone unheard.

From Iran, once again, we bring readers Eira’s beloved comic, Ruhi & Riaz. In this latest installment, Ruhi & Riaz reflect on the devastating impact of the Iran-Iraq war, on the Bahá’í community of Iran.

Also from Iran come the two essays we feature in the “Voices of Iran” section, one heartbreaking and the other heartwarming. In “The Holiest Part of the Desert,” Nava tells a poignant tale about a visit to a government-designated Bahá’í graveyard in the middle of the desert; and in “A New Qiblih,” Nahal Lofti tells a lighthearted story about her grandfather’s conversion to the Bahá’í Faith as a result of a dream.

We round out this issue by taking a look in our book review section at an important little book reissued by Kalimat Press in honor of the centenary. Including a compilation put together by Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield, The Passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, bears revisiting for its detailed account of the responses to and events surrounding the passing of the Master.

Once again, we must thank Ann Sheppard for capturing beauty in the remarkable photographs that appear on the pages of this issue.

In these days of world-encircling frustration in response to an ongoing global pandemic, a climate gone wild, and a multitude of senseless wars, let us take time to reflect on how we might nurture the virtue of trustworthiness, a virtue upon which the very survival of our planet depends. As we go forward in our lives, let us hold before us Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of “one of the Beauties of the Most Sublime Paradise” and let us build, with vigilance and with care, every one of our treasured relationships on the firm, the unshakeable foundation of trustworthiness.

— SLH

by Tami Haaland

Nearly November, the sun beats on mums

alive with honey bees, rising and landing

as though no cold mornings can touch them,

as though they will never stiffen into frost

and hang on flower stems like little rock hearts.

A butterfly, too, its end delayed or

maybe a late appearance, the smallest larva

finally hatched and lovely in its brown

mottled coat. The scent rises, lavender

and fall daisies, blooms opened wide

like children come alive in cold weather.

How can I stop staring, sun on my face?

How can I move toward what comes next?

Rather wish for the perpetual—tomatoes still

on the vine, zucchini and eggplant flowering,

bees elated in this momentary dance.

... (continued)

In February, I had a chance to speak with Tami Haaland, former poet laureate of Montana (2013-15) and the author of three poetry collections .... She is a professor of English at Montana State University Billings and currently serves as Interim Dean of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences.

Sandra: You write a lot about your experience as a woman — as a mother, a daughter, a caregiver — but you don’t seem inclined to delve into gender politics; instead, you seem to use those experiences as a starting point for reflection on the inner life. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Tami: It’s the world from which I express myself; it’s my experience. I grew up in a very rural area, and there were certain assumptions about what women did and didn’t do. It was fine to be physically strong, but there were not that many options for how to live your life. I think I’ve always, from a very young age, been thinking about what it means to be a woman and expanding that vision and speaking about the interior life. In my public life, I speak out about the disparity in the treatment of women and men. My sons grew up knowing that men and women are equal and were later startled when they encountered classmates who believed otherwise.

... (continued)

by Harriet Fishman

Your eyes, full of

pain and joy

seem to cry and laugh

all at once

I see the smile upon your lips

and might not guess

you were imprisoned

an exile who traveled on foot

through bitter cold terrain

barely enough to eat

I might never guess the story

... (continued)

by Susan Mottahedeh

As we near the end of this centenary year in which we have been called to profound reflection on the life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and on the Covenant at whose center He stands, I thought it fitting to reflect on an excerpt from Tablet # 29, which appears in the recently publishing volume of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Writings, Light of the World. In this excerpt, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá tells us that, as human beings, we have a “twofold station.” One could have imagined Him saying a dual nature. But the choice of the word “station” is noteworthy. A ‘station’ is a place or position in which something or someone stands or is assigned to stand or remain. But this “station” is not one in which we, as human beings, will remain: it is only a starting point, a point of departure as we set out on our journey either to move closer to God or further away. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá tells us, both options are available.

He also tells us that the “station” or place from which we begin our journey is “twofold,”

... (continued)

by James Andrews

The thick stone of the walls

in a room small and tight

as a prison cell, cannot muffle

the clatter of the cart

as it travels along the path

... (continued)

by Nahal Lofti

“I was saying my prayer as the sun was about to rise, but to my surprise I realized I was standing facing a totally different qiblih.” These are the exact words my great grandfather used when describing his bizarre dream to Mr. Faizí. At that time, it had been more than six months since Mr. Abu'l-Qásim Faizí had moved to Najaf Abad, a county in Isfahan Province, to share Bahá’u’lláh’s message with the people of the town. Mustafa Lotfi, my great grandfather, was a well digger and one of the most stubborn people you could imagine. He did not believe anything Mr. Faizí told him until one night a dream changed everything.

... (continued)

by Richard Hollinger

Rosey Eva Pool led an unusual life that intersected with some of the most important social and political movements of the twentieth century. Born in Amsterdam in 1905, Pool was raised in the Jewish quarter of the city by secular Jewish parents who were active in the socialist movement. Her exposure to both Judaism and socialism likely contributed to the development of an international perspective as well as a passion for social justice.

From an early age, Pool seems to have had a broad interest in the arts, especially the performing arts. Her involvement with labor and socialist organizations provided her with opportunities to perform on stage as a musician, actress, story-teller, and reciter of poetry. She also did some public speaking in the same context. Pool attended college to become credentialed as a teacher, but went on to study German language and literature, developing a special interest in poetry. She later recalled that while at college, she read a poem by the Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen, in which he recalled a childhood trauma he experienced when a white child called him “nigger.” The poem resonated with Pool’s own experience as a child who was often teased and so stimulated an interest in African-American poetry that would grow over time.

In 1927, Pool moved to Berlin, where she engaged in further academic studies in English, folklore, Spanish and French, and worked at various jobs, including as a language teacher and translator. According to one account, she wrote a Ph.D. dissertation on African-American poetry while in Berlin, but the dissertation has not been located. She appears to have remained involved in socialist activities and sometimes wrote articles for the Dutch press about films and plays with social justice themes. In 1932, she married Gerhard Kramer, a lawyer; however, they separated the following year. Subsequently, she lived with Lena Fischer and both appear to have been part of the lesbian subculture that emerged in Berlin during this period. As the Nazi Party grew in power, Pool and Fischer made plans to move to Amsterdam, but before they could translate these plans into action, Fischer was arrested. She was never heard from again.

... (continued)

by Imelda Maguire

That sensation — hand on my head —

lightly touching,

words I could hear,

but not understand —

then.

... (continued)

by Anton Floyd

....In the mid-nineteenth century, my mother’s French-Lebanese family was subject, as Christian Maronites, to intermittent pogroms in Lebanon. The family left Tyre and Sidon for Egypt and Palestine. One branch settled in Haifa, Palestine but they were forced out of their home on Mount Carmel in 1948 by the newly-formed State of Israel. The Suez Crisis brought my family from Egypt to Cyprus and that is where I grew up. I lived through the Cyprus War of Independence during which both of my older brothers were wounded.

In 1963, after a night of fierce intercommunal fighting we were forced, at gunpoint and with five minutes notice by Turkish militiamen, to leave our Nicosia home. Many of our neighbours lost their lives on that night of trauma. We never returned to that home.

... (continued)

by Valerie Senyk

Lost we are

wanderers in our own deserts

looking for footsteps to follow

not those black tracks

not those muddy bumps

not those bird scratchings

... (continued)

by Eira

... (continued)

by Jim Burke

Falling Into Place is an assured and illuminating poetry debut by Anton Floyd, an Irish poet who is a Levantine mix of Irish, Maltese, English and French Lebanese. Born in Cairo, Egypt and raised in Cyprus, Floyd experienced firsthand the Cypriot struggle for independence. The title, Falling Into Place, carries connotations of innocence, love, family, and place, each revealing a spiritual affinity with mutability and loss.

... (continued)

by Sandra Lynn Hutchison

“Gardening,” May Sarton writes, “is an instrument of grace.” And where there is grace, I might add, there is the potential for a change so radical it might better be described as transformation. Such change may seem miraculous, sometimes even inevitable: no matter how hard we try to resist it, change will come, whether we want it or not. In literature and in scripture, the garden often serves as the scene of such transformation. I think of the “secret garden” in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel of the same name, of the transformation of the sickly young orphan from India into the robust, nature-loving child who finds friendship in a Yorkshire garden; and of Elizabeth, the heroine of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, who reconsiders her initial negative impression of Mr. Darcy when she surveys his grounds, his gardens. And who can forget Titania, the Fairy Queen in Shakespeare’s delightful comedy, a compelling character whose judgment is so transformed by a love potion made from a flower plucked from a woodland garden, that she falls in love with a man with the head of a donkey!

... (continued)

by Anthony A. Lee

The guests were seated

in suits and white afternoon dresses.

Smiles and nods and pleasant phrases.

Then he stood up and asked:

“Where is Mr. Gregory?”

as though that were not unusual or new.

The ladies froze in their seats.

The gentlemen looked away.

Gregory was not invited, no one dared to say.

But he was the host, after all, at any table.

A place was made, a new guest welcomed.

Convention shattered, hell broke loose,

order collapsed, tradition displaced.

The table overturned, the china broke to shards.

They all rushed inside, uninvited and unwashed,

diseased, common, baseborn,

the crowd of humanity—

ignorant and unmannered—given

a place at his table.

... (continued)

Sweet Grass, Oil, 6" x 6"

Sweet Grass, Oil, 6" x 6"

by Pam Jackson

Leo and Margaret celebrating the grand opening of Neda’s Sweet Grass pharmacy in M’Chigeeng First Nation. Leo had an herb table out on display and some really good cedar tea for all those who stopped by.

... (continued)

Water Messengers

Water Messengers

by Nikki Manitowabi

... (continued)

by Nava

The Bahá’í cemetery lies three kilometers outside the city. To reach the cemetery, you have to drive through a barren desert. The landscape is not beautiful. There is nothing to look at besides a single railway track on the right side of the road. If you are lucky, you will see a train passing by. When the trains do pass, it is as if they come only to remind those of us who drive the road to the cemetery that life in this world is not permanent; like the trains that come and go, we will start our journey in this world, and disembark when we reach our destination, the next world.

... (continued)

As a tribute to this special year, we look back on a book first published in hardcover by Kalimat Press in 1991 and reissued this past year in paperback to mark the hundredth anniversary of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s passing. One can scarcely think of a better way to round out a year devoted to reflection on the Master’s life than by reading these accounts, compiled by Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield, of the remarkable impact ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had on all who had the good fortune to encounter Him.

In this book, we see the Master, a figure completely unique in religious history, through the eyes of His broken-hearted followers. While tears are sometimes thought to blur the vision of the mourner, in these accounts, tears seem to bring the scene more sharply into focus. How different is life without ‘Abdu’l-Bahá! As these mourners attest, His absence leaves a space that can never be filled. Not that there was ever any doubt about this in their minds, but for those who were living in or visiting the holy land at the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s passing, the sorrow of loss seems to make feelings of love even keener.

... (continued)