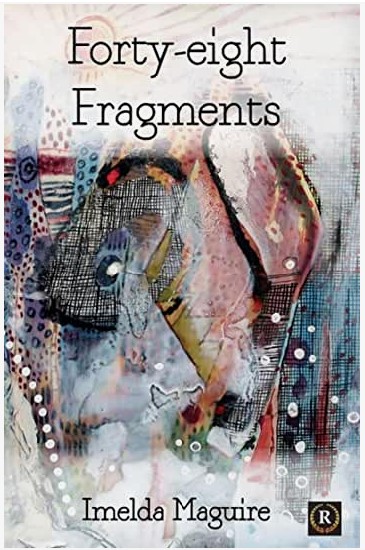

Forty-Eight Fragments

by Imelda Maguire

Review by ANTON FLOYD

Imelda Maguire is a poet. This is what she is rather than just what she does. This is a subtle distinction as her poems come across to me as true to the experience that inspired them and that is really the primary measure of judgment for good poetry: as Robert Frost said, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.” This is not to say that Imelda’s third collection Forty-eight Fragments (Revival Press, 2022) is full of tears. It isn’t. What it does is hold the mirror up to her nature, which is an engaged, gentle, and compassionate one. The collection, then, can be read as fragments, as presented, but when the “fragments” are read as poems in sequence, they generate a reflective memoir of a self as an integrated being.

We all live at slightly different wavelengths. Poetry is one of the ways in which we can tune into other lives and feel a sense of connection. On reading these forty-eight poems, which Maguire modestly refers to as “fragments,” we gain insight into the spiritual self of the poet. And connection in its many variations seems to me to be the unifying theme in Maguire’s poems, which explore immanence and transcendence, family, memory, and nature. While the material world and the society we encounter in the poems is Ireland and Irish, the human dimension of the poems has universal appeal.

In “That Unknown Sorrow,” Maguire catches the reader off guard, with her playful exploration of the Idea of exulansis, a neologism Invited by John Koenig’s in his Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows in an attempt to define “the tendency to give up trying to talk about an experience because people are unable to relate to it.” From the title we can rightly expect the poem to deal with some subjective experience of trauma or unspeakable loss and, indeed, the first stanza more than suggests this:

There is a sense I carry -

wear like a fine shawl,

now it has a name - exulansis -

a story I have told myself over

and over, that what’s in my heart

is too weird, too much

for others to take on.

Yet instead of that trauma or loss, what “stays, hidden, almost/lurking, waiting its turn/ to be released . . . is, after all, only love.” With a single word, Maguire articulates what lies at the heart of her world: it is love that defines her life-affirming poetry. Take the poem “What Mother Said.” In an easy conversational style, Maguire recalls her mother’s response to the self-doubt of her teenage daughter:

you don’t have to measure,

you just need to know how you want it to turn out,

and that it’s fine if something’s different every time -

would you really want it to always be the same?

She deepens the recollection in the following stanza:

Some things she didn’t say: - she just implied, or I took it as read,

that it is good to take pleasure in what’s good, that a little pleasure

can be great, if you go fully into it like she would with ice-cream.

The final stanza completes Maguire’s loving portrait of her mother:

We were there again this summer, my sister and I.

We showed my son the place, the very bench she’d sat on.

there should be a statue, or a plaque, engraved with the picture -

old lady with a lap full of ladybirds, all over her blue summer-dress

and what she said:

“Lovely” she said. “Lovely.”

There are other engaging poems that never stray into nostalgia precisely because they demonstrate the poet’s eye for telling detail and her ability to make the ordinary extraordinary. These poems tell us as much about the poet as they do about her lively family. In “Sundays,” for example, Maguire explores the different memories two siblings have of their musical father.

My brother’s memory

is of the same scene,

and yet, when I asked

‘Do you conduct the music,

like he used to do?’

he replied, ‘No, I whistle

like he used to do.

Don’t you?’

A capacity for keen observation and an ability to remember clearly, vividly shows itself In the poems of this volume. In “What Taps Me On The Shoulder,” for example, past and the present coexist in the poet’s consciousness. And in “Quirks,” Maguire recalls her mother’s way of “whistling, greeting magpies, /eating jam off the spoon,” and how “as we drove up the country, she’d read aloud the signs we passed. / ‘Tubbercurry, 10 miles, / Joanne’s hair salon, /Cabbage plants for sale.” For me the telling lines of the poem are these:

Big signs were often ignored

in favour of the one

that just struck her

for no known reason.

It seems to me that these lines perfectly describe Maguire’s own habit of “noticing.” In this, she reminds me of the great Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh in poems such as “Advent”and, especially, “The One.”

In the section “Goose Tribe and Ancestry,” each poem, with a customary light touch, is organised around a central idea. “Goose Tribe,” which Is about a family reunion in Canada, ends:

we stay together, propelled by blood

and sharing,

held aloft by mother-lines,

grandmother-lines.

We fly.

In “Ancestry,” the poet reflects on her personal history, the genetic pool out of which her story arises and people and places that have nurtured her as a poet. The fourth and final stanza begins with “One of this poem’s grandfathers/grew things” and ends as follows:

and some of those trees still sing

and tell their poems to the breeze,

and sing over the saplings

just now beginning to stretch

into the light, to sing

their own songs,

to chant their own verse.

Here we can catch something of Maguire’s nature, typical of her Irish character, namely her wish to pass the love of poetry on to the next generation. Inherent in this impulse, as in all the poems in the collection, is the sense that Maguire writes not just to communicate an experience, but to live that experience more deeply. Poetry may have its limits as a means of communicating experience, but it is a powerful and effective way to live and re-live life.

Nature is a presence in almost all of the poems, giving the volume a clear sense of place and context. No fewer than eleven poems take nature as their central theme. Trees hold pride of place in her world. In a poem such as “Tree Song,” the poet affirms life, drawing attention to the truth that the seasonal cycle will go on, with every root casting a new shoot. In “Summons,” the poet writes of the feeling of being drawn to a chestnut tree and watching it change. The affinity she feels for the trees calls forth nostalgia:

They tell me that I am of them,

They call me Sister now, not child, and now

it seems the gifts they offered in childhood

have turned to tears, falling,

falling - golden tears.

A significant feature in this collection is the value Maguire attaches to human potential, her own included. She asserts a positive sense of self in the spare and powerfully expressed “Now I’m a Warrior:”

No sword, no bow,

no spear,

but pen and ink

to wield.

Now I am a warrior,

one-breasted woman.

Now I am an Amazon.

There are companion poems to this one, poems that one might consider even more spiritual in what is a very spiritual collection. That is to say poems that come seem to bypass the mind and open the heart to a vital, motivating force. In poems such as “Detour,” “Soulskin,” “Sealskin,” and “In Liminality,” and in devotional poems such as “Shrine of the Bab” and “Visitation,” Maguire awakens the reader a sense of mystery and wonder, of awe and a deeper knowing.

The most powerful poem in this category perhaps is “One Day.” Here she uses narrative and the sensual freshness of D.H. Lawrence to tell of an inner sea “[r]unning through her veins, the wash/ and swish of waves sound/ like my sleeping self.” The poet senses that there is something beyond, around, and also within her -- some great power. The final stanza is confident and welcomes the anticipated mystery by describing an act that Koenig might call liberosis as the poet anticipates, with joy, the casting off of her human flesh:

I come to the shore to watch

and listen

I wear my shoesOne day, I will slip them off,

I wear my coat.

the coat, the shoes, the clothes,

and I will swim.

Language, in the course of everyday usage, can become battered and bruised. But a poet has to trust that language can perform miracles, can rescue and heal. Primarily, it can rescue us from drowning in a sea of familiarity. Maguire does just that; she uses language to “rescue” us from the familiar. Her language has the simplicity of her truth. As Philip Larkin said of his own poetry, it has the merit of “cutting out obscurity . . . references to literature and mythology which you cannot be sure the reader knows.” Maguire writes in a language ordinary people can access and enjoy.

This collection of poems, with its lovely cover painting by Gerry O’Mahony, itself a fragment, shares a common theme of the love found in family, in nature, and, in solitary moments, through memory. In Forty-eight Fragments, Maguire reflects on her experiences with a welcome optimism and childlike wonder. In a fragmented world, this collection of Forty-eight Fragments offers its readers a gift by presenting the possibility of an integrated and connected life. I am happy to recommend it as a companion and a guide for those who seek such integration and connection.

Anton Floyd