Art and the Creative Process: An Interview with Hooper C. Dunbar

by NANCY LEE HARPER

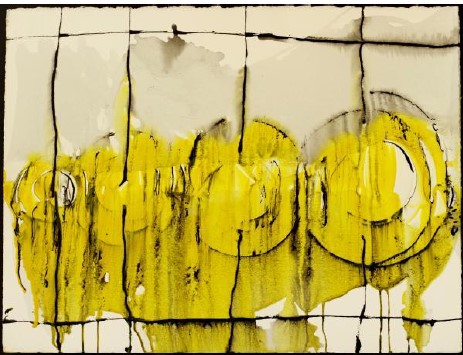

Pulsing Icons, 2009, Acrylic on Canvas, 60" x 48"

It was a beautiful spring day in April 2014 when Hooper Dunbar and I sat down to talk about spirituality, service, and the work of an artist. A budding actor who had worked in television, on Broadway, and in films with Columbia, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Twentieth Century-Fox, Hooper had decided to trade in the stage for pioneering service for the Bahá’í Faith. Ironically, in doing so, he became an actor on one of the largest stages in the world, that of the global Bahá’í community — and an artist of a different sort, producing a large body of paintings.

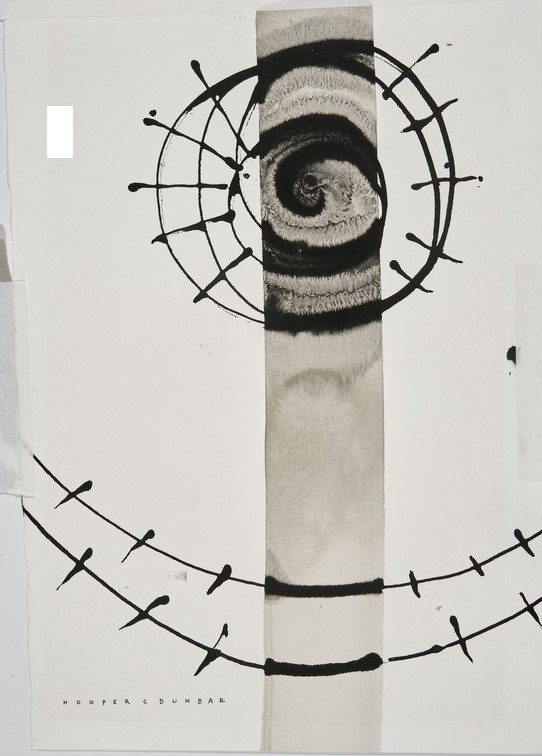

Inner Position, 2003, Acrylic on Paper, 30" x 22.5"

As we began our interview, Hooper pointed to a vase of gorgeous yellow blooms and said, “These roses only grow at Ridván.” As I pondered the auspicious timing of those blooms, I was reminded of how the threads of our lives are woven by destiny into a rich tapestry, for it was Hooper himself who encouraged my husband and I to pioneer to Argentina during the early 1970s. There, at our home in Trevelin, we had two nine-pointed-star rose gardens. The rosebush that grew to be the largest was planted by Dr. Rahmatu’llah Muhajir, Hand of the Cause. Coincidentally, as a member of the Continental Board of Counsellors, Hooper had occasion to travel, assist, and translate for Dr. Muhajir in South America.

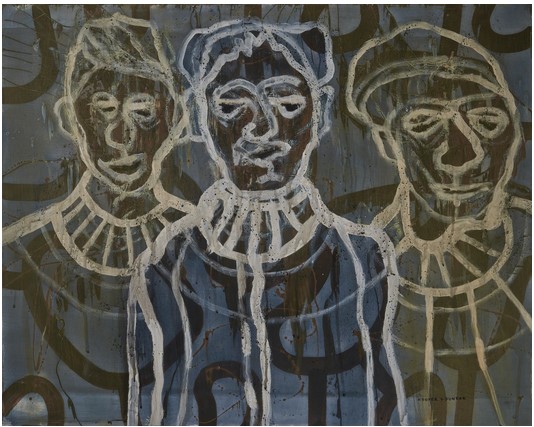

Three Kings, 2013, Acrylic, 48" x 60"

In this interview, I touch upon the themes of life, death, creation, inspiration, transformation, and more in an effort to trace Hooper Dunbar’s journey, as an artist who draws upon the spiritual forces generated by Bahá’u’lláh’s Word to create his work. More than forty years and another pioneering post later — one that we filled in Portugal in 1992, the holy year marking the centenary of the passing of Bahá’u’lláh — my husband and I find ourselves back in the United States and fortunate to be serving our faith in northern California, near Hooper and his wife, Maralynn — an auspicious bloom, indeed!

NLH: Thank you for your time and for consenting to this interview in your Granite Bay studio, surrounded as we are by hundreds of your interesting paintings and countless memories. You are a most distinguished Bahá’í, having served all of your adult life in many capacities, from pioneer, educator and author, to appointed Auxiliary Board Member for Protection, member of the Continental Board of Counsellors, founding member of the International Teaching Centre, and, finally, member of the Universal House of Justice. For over thirty years in the Holy Land, you gave weekly youth classes in which you offered instruction to more than 6,000 Bahá’í youth. You are an author of various Bahá’í books, including Companion to the Study of the Kitáb-i-Iqán and Forces of our Time and have taught many courses, yet you have managed to find time to develop your artistic side, working in arts such as film, theater, photography, sculpture, music, and most of all, painting. Taking into consideration the amount of time that art requires and keeping in mind the words of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that art is service, could I ask you how your Bahá’í work has contributed, influenced, or otherwise been related to your artistic work?

HCD: I was very keen about the arts before I heard of the Bahá’í Faith. I had been an actor, had done scenic design, had worked with a modern dance theater. I went to New York and there I painted privately; that is to say, I felt that the paintings were so personal — small abstract and expressionist paintings they were at that time. I lived in a small, cold-water flat. When I first heard of the Bahá’í Faith and was attracted to it, I did some line drawings as an immediate response to the and dreams I was having and the strong feelings I was experiencing. Through the Bahá’í Faith, I felt all of those creative fields potentially animated. Then, through my service, I collected endless visual images, whether in the rain forest in Nicaragua, where I was for five years, or in the Andes and the Amazon basin in South America, and in so many other places. I stored a lot of those visual materials for eventual use. I hadn’t the possibility of painting very regularly in the pioneering field. Some of those images came back to me some years later as Maralynn and I became central to Bahá’í book publishing in Latin America, translating and reviewing books. Actually, I designed books there for a while, which put me in good stead at the World Center for the Universal House of Justice during the twenty or so years that I served on that body, which included the design and launching of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. After our move to the World Center I did some ten years of watercolors, what I call “polite” watercolors — natural scenes — and ink sketches of a number of Holy Places in the 1970s and up to 1988. After my election to the Universal House of Justice, I had more space available to me that I could use for a studio and so I went on to paint larger abstract works in the few free hours a month I had. Donald Rogers, or Otto Rogers as he is known in the art world, was then a Counselor at the International Teaching Centre in the Holy Land. He had a large studio, which he financed himself, as the World Centre did not have such facilities. There were some original Bauhaus-designed houses in Haifa and Don’s studio was housed in one of them. It had a glorious multi-floored space with arches and views of the sea. I started with some abstracts, but, again, I kept them to myself. Somehow, I had fused in my mind Shoghi Effendi’s comments about the corruption of modern art with abstract painting, so I was hesitant about whether I should be doing or showing this kind of painting. Certainly, I had the urge and compulsion. Don’s explanations freed me from that. He was an abstract painter too. I realized then that the products of the mind in all fields of human endeavor were renewed with the coming of the Twin Manifestations, so also the field of art went through a transformation. I have since had opportunities to explore more carefully the directions that Cezanne took, and the first Cubists — Picasso and Braque — and to consider the influence that the New Age subsequently had on them and their work. It freed me up. I would say and do believe that my motivation comes from the energy of the Bahá’í Faith. If one has a life of devotion and also reflection — of thinking and trying to translate the intuitive knowledge in one’s own consciousness, into action — then surely the influence of one’ faith is an important factor. I think that during that period, working with the youth and so on, the transformation of knowledge became an important factor — looking at things, seeing the natural world. In one way, the natural world is a terrible distraction, the source of all temptation, but the flip side is that when you reach a certain perspective, a certain understanding, that same world becomes the face of God. It’s the amalgamation of all the signs of His names there to be witnessed, drawn on. In that sense, it is a primary source of art. You know that wonderful quotation of Bahá’u’lláh, of what the Word produces in the minds of writers or scientists or artists. In each one, the endowments He has given us, the gifts He has left us, are animated by the powers of the Word of God, which, obviously, are not simply verbal, but inherent forces — creative energies.

NLH: Bahá’u’lláh Himself was a poet. How has your work in other art forms contributed to your painting, artistic perception, and creation?

HCD: Music has had a great role. I like the presence of music. One of the gifts I got in the Holy Land was through Douglas Martin, a colleague who also on the Universal House of Justice, who asked me which operas I liked best. At the time, I said, “I don’t like opera; I turn it off as soon as it comes on. I can’t bear it.” And he responded, “You are missing about half your life, you know.” So I asked, “Well, what should I start with?” I liked some of the cantatas of Bach, his choral works and those of Handel, so Douglas loaned me some recordings, a couple of operas, and urged me to listen to them and see how I felt, which I did, until I became familiar with them. I was not totally convinced, but it made opera a little easier for me to listen to until I got a set of videos of Verdi’s Don Carlos. That was very intense. The CDs came with interviews with the conductor, the singers, the musicians, and with all of that I realized the richness of it. Douglas always said, “This is the king of arts. All of the arts are in opera.” And gradually my ears started attuning, and I became very avid about that. I was helped by a few Bahá’ís who shared videos of operas with me. I later made it a point of attending operas. I have been to most of the great opera houses in Europe for at least one performance. Vienna is wonderful. The most exciting opera I ever went to was in Geneva, though, a Don Carlos that put your hair on end. I saw a lot of good opera in Tel Aviv as well. The Israeli opera was quite lively. There was a marvelous Madame Butterfly, and a Turandot. All that contributed. Then I got to know Lasse Thoresen and was introduced to post-classical music, though I had had some introduction early on because of a play I performed in New York City in 1955, which was the first play to have electronic music, the music of Pierre Schaeffer. The whole score was his. It was quite arresting. Alan Hovhaness was the musical director. He spoke to the cast — a very intriguing, austere figure. The play was by Paul Goodman and about the appearance of a new Prophet in New York City in modern times. It had a number of avant-garde elements in it. Anyway, it introduced me to a new kind of music. Merce Cunningham designed the movement for the piece and choreographed it. There was a majesty in the movement. It was interesting to know these people.

NLH: You were very fortunate. Isadora Duncan was before that.

HCD: Yes, she was much earlier. While I was in New York, I went up to the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival and saw Jose Limon’s work, which I liked very much. His dancing, and that of the Lester Horton Dance Theater I was associated with in Los Angeles, were most interesting to me. Horton launched Alvin Ailey. He was a lead dancer and went on to found his own international group. Others associated with Horton were Carmen De Lavallade, who married Geoffrey Holder. They became very important dancers in New York.

NLH: While we do not as yet have what the world might recognize as Bahá’í art, what or who are the influences in your current work as a painter?

HCD: Though we don’t yet have coherent Bahá’í art, we certainly see a Bahá’í influence on various Bahá’í artists. And Shoghi Effendi said that he hoped that the present-day Bahá’í artists would do more and more to reflect the light of the revelation in their work. Such work doesn’t take on the broad characteristics of, say, Hindu or Islamic art, in other words, something that is immediately identifiable. That kind of evolution will take quite a while.

NLH: Regarding contemporary painters, which ones influence you today?

HCD: Of course, Donald Rogers had an immediate influence on my work. I was very geometric at first, and then he urged me to loosen up. “You’ll have to become yourself,” he said. That helped a lot. From a young age, I was always attracted to Paul Klee’s work.

NLH: And Mark Tobey?

HCD: I regretted that early on I did not know enough about him to go and meet him. I wish I had. I did read a letter that he had written to one of the early Bahá’ís who shared it with an informal group at the Orrington Hotel in 1956. And it was dynamic — about art and the spirit of the Bahá’í Faith. I hope we will have more of his correspondence and letters. Recently, I saw a volume of correspondence between Tobey and Lyonel Feininger had been published, which is quite interesting. And, of course, Mark Tobey leads to Jackson Pollock. My work may be seen as derived from them. I think that within the scope of “drip” painting, we have the large scale of production by Pollock, which can be seen to derive from the smaller, more detailed pioneering work of Tobey. In my own work, I find a more open portrayal of these earlier motifs.

NLH: So would you say that your painting takes up where Tobey’s left off?

HCD: Well, not left off, because it is not a continuum for me. Related to that, I admire a large collection of painters — a lot of the Expressionists, de Kooning, others. I like Braque’s work very much. I like Juan Gris’s work. I don’t paint like him, but his work has much appeal. Richard Diebenkorn attracted me early on. I really like his work. Those are some painters that readily come to mind.

NLH: What role does nature play in your painting?

HCD: Nature is, of course, wondrous. I was talking to Maralynn about how we look at flowers, and thought to myself isn’t nature wonderful? We are schooled in how amazing nature is without always realizing that it is an expression of God. Nature is God’s will and His Face. It is our immediate contact with our Maker. People ask, “How can I know God?” But it is in our faces constantly if we but contemplate the signs of God, as Muhammad commanded us to, contemplate in the sense of recognize and appreciate them and be humbled by them and be thankful in witnessing the extraordinary profusion of God’s endless creativity and wisdom. There is always that. It is not necessarily a “copying,” although I did very much enjoy the years I painted in watercolors. They had some abstract elements to them, beach scenes, mountains, lakes — the kind of nature that adapts itself to watercolor abstraction.

NLH: Is your preferred medium now acrylics?

HCD: Yes, I have no patience for the smells and drying time of oils, although I love working with them. My work is very spontaneous. I like to work when there is hot sun and I can take a painting out into the light for one layer to dry, and then bring it inside again to continue the thought process I have set in motion at a new level. But if I have to leave it for ten days to dry, then I might as well start something new.

NLH: On your website, you classify your paintings as “Reflections,” “Mindscapes,” “Introspections,” and “Becomings . . . .”

HCD: “Figurations” is one too — face, figures, sprites. The others are just suggested groupings of paintings that seem to cluster around one another.

NLH: What is the role of light in your conception of a new work?

HCD: Light is important. It is a major factor, which, without having to unduly think about it, becomes the major organizer of a painting. Light has much to do with contrasts, the chiaroscuro effect of the elements of the painting. I have painted a lot of very dark paintings, and I find that there is often light in darkness, suggestions that you can bring out. I have a broad colour palette, not limited in any way.

HCD: I was very keen about the arts before I heard of the Bahá’í Faith. I had been an actor, had done scenic design, had worked with a modern dance theater. I went to New York and there I painted privately; that is to say, I felt that the paintings were so personal — small abstract and expressionist paintings they were at that time. I lived in a small, cold-water flat. When I first heard of the Bahá’í Faith and was attracted to it, I did some line drawings as an immediate response to the and dreams I was having and the strong feelings I was experiencing. Through the Bahá’í Faith, I felt all of those creative fields potentially animated. Then, through my service, I collected endless visual images, whether in the rain forest in Nicaragua, where I was for five years, or in the Andes and the Amazon basin in South America, and in so many other places. I stored a lot of those visual materials for eventual use. I hadn’t the possibility of painting very regularly in the pioneering field. Some of those images came back to me some years later as Maralynn and I became central to Bahá’í book publishing in Latin America, translating and reviewing books. Actually, I designed books there for a while, which put me in good stead at the World Center for the Universal House of Justice during the twenty or so years that I served on that body, which included the design and launching of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. After our move to the World Center I did some ten years of watercolors, what I call “polite” watercolors — natural scenes — and ink sketches of a number of Holy Places in the 1970s and up to 1988. After my election to the Universal House of Justice, I had more space available to me that I could use for a studio and so I went on to paint larger abstract works in the few free hours a month I had. Donald Rogers, or Otto Rogers as he is known in the art world, was then a Counselor at the International Teaching Centre in the Holy Land. He had a large studio, which he financed himself, as the World Centre did not have such facilities. There were some original Bauhaus-designed houses in Haifa and Don’s studio was housed in one of them. It had a glorious multi-floored space with arches and views of the sea. I started with some abstracts, but, again, I kept them to myself. Somehow, I had fused in my mind Shoghi Effendi’s comments about the corruption of modern art with abstract painting, so I was hesitant about whether I should be doing or showing this kind of painting. Certainly, I had the urge and compulsion. Don’s explanations freed me from that. He was an abstract painter too. I realized then that the products of the mind in all fields of human endeavor were renewed with the coming of the Twin Manifestations, so also the field of art went through a transformation. I have since had opportunities to explore more carefully the directions that Cezanne took, and the first Cubists — Picasso and Braque — and to consider the influence that the New Age subsequently had on them and their work. It freed me up. I would say and do believe that my motivation comes from the energy of the Bahá’í Faith. If one has a life of devotion and also reflection — of thinking and trying to translate the intuitive knowledge in one’s own consciousness, into action — then surely the influence of one’ faith is an important factor. I think that during that period, working with the youth and so on, the transformation of knowledge became an important factor — looking at things, seeing the natural world. In one way, the natural world is a terrible distraction, the source of all temptation, but the flip side is that when you reach a certain perspective, a certain understanding, that same world becomes the face of God. It’s the amalgamation of all the signs of His names there to be witnessed, drawn on. In that sense, it is a primary source of art. You know that wonderful quotation of Bahá’u’lláh, of what the Word produces in the minds of writers or scientists or artists. In each one, the endowments He has given us, the gifts He has left us, are animated by the powers of the Word of God, which, obviously, are not simply verbal, but inherent forces — creative energies.

NLH: Bahá’u’lláh Himself was a poet. How has your work in other art forms contributed to your painting, artistic perception, and creation?

HCD: Music has had a great role. I like the presence of music. One of the gifts I got in the Holy Land was through Douglas Martin, a colleague who also on the Universal House of Justice, who asked me which operas I liked best. At the time, I said, “I don’t like opera; I turn it off as soon as it comes on. I can’t bear it.” And he responded, “You are missing about half your life, you know.” So I asked, “Well, what should I start with?” I liked some of the cantatas of Bach, his choral works and those of Handel, so Douglas loaned me some recordings, a couple of operas, and urged me to listen to them and see how I felt, which I did, until I became familiar with them. I was not totally convinced, but it made opera a little easier for me to listen to until I got a set of videos of Verdi’s Don Carlos. That was very intense. The CDs came with interviews with the conductor, the singers, the musicians, and with all of that I realized the richness of it. Douglas always said, “This is the king of arts. All of the arts are in opera.” And gradually my ears started attuning, and I became very avid about that. I was helped by a few Bahá’ís who shared videos of operas with me. I later made it a point of attending operas. I have been to most of the great opera houses in Europe for at least one performance. Vienna is wonderful. The most exciting opera I ever went to was in Geneva, though, a Don Carlos that put your hair on end. I saw a lot of good opera in Tel Aviv as well. The Israeli opera was quite lively. There was a marvelous Madame Butterfly, and a Turandot. All that contributed. Then I got to know Lasse Thoresen and was introduced to post-classical music, though I had had some introduction early on because of a play I performed in New York City in 1955, which was the first play to have electronic music, the music of Pierre Schaeffer. The whole score was his. It was quite arresting. Alan Hovhaness was the musical director. He spoke to the cast — a very intriguing, austere figure. The play was by Paul Goodman and about the appearance of a new Prophet in New York City in modern times. It had a number of avant-garde elements in it. Anyway, it introduced me to a new kind of music. Merce Cunningham designed the movement for the piece and choreographed it. There was a majesty in the movement. It was interesting to know these people.

NLH: You were very fortunate. Isadora Duncan was before that.

HCD: Yes, she was much earlier. While I was in New York, I went up to the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival and saw Jose Limon’s work, which I liked very much. His dancing, and that of the Lester Horton Dance Theater I was associated with in Los Angeles, were most interesting to me. Horton launched Alvin Ailey. He was a lead dancer and went on to found his own international group. Others associated with Horton were Carmen De Lavallade, who married Geoffrey Holder. They became very important dancers in New York.

NLH: While we do not as yet have what the world might recognize as Bahá’í art, what or who are the influences in your current work as a painter?

HCD: Though we don’t yet have coherent Bahá’í art, we certainly see a Bahá’í influence on various Bahá’í artists. And Shoghi Effendi said that he hoped that the present-day Bahá’í artists would do more and more to reflect the light of the revelation in their work. Such work doesn’t take on the broad characteristics of, say, Hindu or Islamic art, in other words, something that is immediately identifiable. That kind of evolution will take quite a while.

NLH: Regarding contemporary painters, which ones influence you today?

HCD: Of course, Donald Rogers had an immediate influence on my work. I was very geometric at first, and then he urged me to loosen up. “You’ll have to become yourself,” he said. That helped a lot. From a young age, I was always attracted to Paul Klee’s work.

NLH: And Mark Tobey?

HCD: I regretted that early on I did not know enough about him to go and meet him. I wish I had. I did read a letter that he had written to one of the early Bahá’ís who shared it with an informal group at the Orrington Hotel in 1956. And it was dynamic — about art and the spirit of the Bahá’í Faith. I hope we will have more of his correspondence and letters. Recently, I saw a volume of correspondence between Tobey and Lyonel Feininger had been published, which is quite interesting. And, of course, Mark Tobey leads to Jackson Pollock. My work may be seen as derived from them. I think that within the scope of “drip” painting, we have the large scale of production by Pollock, which can be seen to derive from the smaller, more detailed pioneering work of Tobey. In my own work, I find a more open portrayal of these earlier motifs.

NLH: So would you say that your painting takes up where Tobey’s left off?

HCD: Well, not left off, because it is not a continuum for me. Related to that, I admire a large collection of painters — a lot of the Expressionists, de Kooning, others. I like Braque’s work very much. I like Juan Gris’s work. I don’t paint like him, but his work has much appeal. Richard Diebenkorn attracted me early on. I really like his work. Those are some painters that readily come to mind.

NLH: What role does nature play in your painting?

HCD: Nature is, of course, wondrous. I was talking to Maralynn about how we look at flowers, and thought to myself isn’t nature wonderful? We are schooled in how amazing nature is without always realizing that it is an expression of God. Nature is God’s will and His Face. It is our immediate contact with our Maker. People ask, “How can I know God?” But it is in our faces constantly if we but contemplate the signs of God, as Muhammad commanded us to, contemplate in the sense of recognize and appreciate them and be humbled by them and be thankful in witnessing the extraordinary profusion of God’s endless creativity and wisdom. There is always that. It is not necessarily a “copying,” although I did very much enjoy the years I painted in watercolors. They had some abstract elements to them, beach scenes, mountains, lakes — the kind of nature that adapts itself to watercolor abstraction.

NLH: Is your preferred medium now acrylics?

HCD: Yes, I have no patience for the smells and drying time of oils, although I love working with them. My work is very spontaneous. I like to work when there is hot sun and I can take a painting out into the light for one layer to dry, and then bring it inside again to continue the thought process I have set in motion at a new level. But if I have to leave it for ten days to dry, then I might as well start something new.

NLH: On your website, you classify your paintings as “Reflections,” “Mindscapes,” “Introspections,” and “Becomings . . . .”

HCD: “Figurations” is one too — face, figures, sprites. The others are just suggested groupings of paintings that seem to cluster around one another.

NLH: What is the role of light in your conception of a new work?

HCD: Light is important. It is a major factor, which, without having to unduly think about it, becomes the major organizer of a painting. Light has much to do with contrasts, the chiaroscuro effect of the elements of the painting. I have painted a lot of very dark paintings, and I find that there is often light in darkness, suggestions that you can bring out. I have a broad colour palette, not limited in any way.

Black & White Figuration, Acrylic

NLH: Did you ever go through a minimalistic stage?

HCD: Well, that black-and-white one. Early on I did some simple black and white figurations. Some of them are still around. Light is the leaven of it all. And I suppose it is in the spiritual sense, too, the thing that animates your thought processes.

NLH: Great composers often work in different ways. For example, Mozart would sometimes hear an entire composition in his head before writing it down. Beethoven, on the other hand, worked and reworked painstakingly until he created a masterpiece.

HCD: And Tchaikovsky would get inspired with a warm bath, or a step off of a carriage.

NLH: What is your preferred working method? Do you have a process that stimulates creativity?

HCD: I don’t paint every day. The urge accumulates in me till I want to paint. I paint in intense periods, then take a break. With all the international travels I am engaged in, sometimes I don’t get to paint for some weeks at a time. When I return to painting, I usually have a settling in period where I modify previous paintings or make some collages or do something to get myself going. Generally, I find after coming back from a trip I say to myself, “You are not a painter. What are you doing?” And I back away from it for days and then, suddenly, it will all start again. Once, the forces of it combine and they are intense, I do one thing after another. I may be doing four or five paintings simultaneously and do that till I reach a point of exhaustion, and then I take a breather again. I know there are other painters who meticulously paint every day, but in me it comes in surges.

NLH: You paint while you are listening to music, don’t you?

HCD: Yes, usually. I listen to contemporary music or opera. I don’t know to what degree that is reflected in the paintings, but I find that it helps to maintain the mood. Oftentimes, it is very useful.

NLH: Do you have any particular techniques that are helpful? For example, some composers use the Golden Section.

HCD: I don’t know how it works. People have commented that oftentimes my work has a three-fold character, but that is just natural. You have one element, then another, then another with the same force, each acting on the other in the same painting. It is mostly intuitive with me. I have had no formal art training outside high school and some advice from Don Rogers and Leonard Herbert, a Bahá’í friend and painter, who passed away in Hawaii. He deepened me in the Bahá’í Faith. I had some art classes with him just after I became a Bahá’í. His wife was my spiritual mother, Jesma Herbert, a member of the first Auxiliary Board for Protection. I first heard of the Bahá’í Faith from Sando Berger, who later died as a pioneer in Puebla, Mexico. He was a painter and a sculptor. I was greatly attracted to the character of this man. When Sando was eighteen, his Jewish family, seeing trouble ahead, sent him from their home in Hungary to New York. He was the only one of them who survived the war. He was a very gifted painter whose work has been exhibited at Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

NLH: Did you hear about the Bahá’í Faith from Sando Berger in New York?

HCD: No, in Los Angeles. Sando just brought it up out of the blue. And he took us to meet other Bahá’ís. Virginia Foster spoke at the first meeting I went to. She was an important teacher in the second Seven Year Plan — a nightingale of a speaker. I heard more about the Bahá’í Faith from her, and then gravitated toward Jesma Herbert in another meeting and became a Bahá’í. I was in film work at the time. My family lived a couple hours away in Newport Beach, and I often slept in an art studio that belonged to Jesma’s husband, Leonard, and would take Jesma to her medical treatment. She passed away after I went pioneering, a very gifted spiritual woman. She had found the Bahá’í Faith in a library. She opened The Hidden Words and knew it was the Word of God. This was years before she found out there was a Bahá’í community. She had been a Theosophist and went on to become the secretary of the National Teaching Committee during the second Seven Year Plan, which was a pretty heavy load.

HCD: Well, that black-and-white one. Early on I did some simple black and white figurations. Some of them are still around. Light is the leaven of it all. And I suppose it is in the spiritual sense, too, the thing that animates your thought processes.

NLH: Great composers often work in different ways. For example, Mozart would sometimes hear an entire composition in his head before writing it down. Beethoven, on the other hand, worked and reworked painstakingly until he created a masterpiece.

HCD: And Tchaikovsky would get inspired with a warm bath, or a step off of a carriage.

NLH: What is your preferred working method? Do you have a process that stimulates creativity?

HCD: I don’t paint every day. The urge accumulates in me till I want to paint. I paint in intense periods, then take a break. With all the international travels I am engaged in, sometimes I don’t get to paint for some weeks at a time. When I return to painting, I usually have a settling in period where I modify previous paintings or make some collages or do something to get myself going. Generally, I find after coming back from a trip I say to myself, “You are not a painter. What are you doing?” And I back away from it for days and then, suddenly, it will all start again. Once, the forces of it combine and they are intense, I do one thing after another. I may be doing four or five paintings simultaneously and do that till I reach a point of exhaustion, and then I take a breather again. I know there are other painters who meticulously paint every day, but in me it comes in surges.

NLH: You paint while you are listening to music, don’t you?

HCD: Yes, usually. I listen to contemporary music or opera. I don’t know to what degree that is reflected in the paintings, but I find that it helps to maintain the mood. Oftentimes, it is very useful.

NLH: Do you have any particular techniques that are helpful? For example, some composers use the Golden Section.

HCD: I don’t know how it works. People have commented that oftentimes my work has a three-fold character, but that is just natural. You have one element, then another, then another with the same force, each acting on the other in the same painting. It is mostly intuitive with me. I have had no formal art training outside high school and some advice from Don Rogers and Leonard Herbert, a Bahá’í friend and painter, who passed away in Hawaii. He deepened me in the Bahá’í Faith. I had some art classes with him just after I became a Bahá’í. His wife was my spiritual mother, Jesma Herbert, a member of the first Auxiliary Board for Protection. I first heard of the Bahá’í Faith from Sando Berger, who later died as a pioneer in Puebla, Mexico. He was a painter and a sculptor. I was greatly attracted to the character of this man. When Sando was eighteen, his Jewish family, seeing trouble ahead, sent him from their home in Hungary to New York. He was the only one of them who survived the war. He was a very gifted painter whose work has been exhibited at Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

NLH: Did you hear about the Bahá’í Faith from Sando Berger in New York?

HCD: No, in Los Angeles. Sando just brought it up out of the blue. And he took us to meet other Bahá’ís. Virginia Foster spoke at the first meeting I went to. She was an important teacher in the second Seven Year Plan — a nightingale of a speaker. I heard more about the Bahá’í Faith from her, and then gravitated toward Jesma Herbert in another meeting and became a Bahá’í. I was in film work at the time. My family lived a couple hours away in Newport Beach, and I often slept in an art studio that belonged to Jesma’s husband, Leonard, and would take Jesma to her medical treatment. She passed away after I went pioneering, a very gifted spiritual woman. She had found the Bahá’í Faith in a library. She opened The Hidden Words and knew it was the Word of God. This was years before she found out there was a Bahá’í community. She had been a Theosophist and went on to become the secretary of the National Teaching Committee during the second Seven Year Plan, which was a pretty heavy load.

Dawn-Breakers

Dawn-BreakersNLH: Recently I saw one of your paintings that was inspired by the Dawn-Breakers. Is this a new phase?

HCD: Which one? There’s this one.

NLH: Yes, it’s that one. That’s recent, isn’t it?

HCD: I think Chad Jones, one of the local Bahá’ís, decided it was the Dawn-Breakers. It has had its influence. The Dawn-Breakers is a source of artistic and literary influences, as Shoghi Effendi suggested. I don’t think the painting is limited to that; I think it is the enhancing of a created space where music and everything else can come out.

NLH: You made a film about your creative process in the Holy Land?

HCD: Some young film makers recorded several episodes of me painting and also talking about my work. It has not yet been finally edited.

NLH: Music and art naturally have elements in common, as well as differences. When I commissioned an artist to make the lid and soundboard paintings for my harpsichord many years ago, I was entranced to find out that, in the baroque view, art was not complete until the sound was made. Charles Wolcott observed that in music there are three protagonists involved: the creator or composer, the performer or interpreter, and the listener or public. In painting, there are two: the creator or artist and the public. In rare instances in contemporary music, such as John Cage’s 4’33’’ — a work of silence, in three movements! — the listener becomes the interpreter. Do you keep the public in mind when creating or do you prefer to convey an internal message?

HCD: I want to be faithful to the vision I have. When I get something that locks together and I feel satisfied, then I hope others will enjoy it. Perhaps they can access through it some of the energies that crystallized there. You know, I view art as, on the one hand, inspiration, and on the other, technique. We all borrow. We are all standing on the shoulders of the artists of the past. Don Rogers said to me early on: “Choose three different painters you like and fix yourself in the middle of them to start.” This is an interesting place to begin. You use a combination of their languages until you find your vision, combine them, and then go on from there to develop your own language and vision.

NLH: What three did you choose?

HCD: I didn’t do it. I had already gotten to the stage where I had a pretty independent idea of what I wanted to do, but there were those who influenced me, such as Don Rogers himself. I find the development of technique very exciting. One progressively acquires skills in the handling of materials. For example, the water color experience was a big help to me in handling acrylic, so that I was not hesitant to use acrylics in a more liquid form. In layering the work, in viscosity, in more liquid form, in solid painting with water spray — all quite exciting, quite revealing, textural stuff.

HCD: Which one? There’s this one.

NLH: Yes, it’s that one. That’s recent, isn’t it?

HCD: I think Chad Jones, one of the local Bahá’ís, decided it was the Dawn-Breakers. It has had its influence. The Dawn-Breakers is a source of artistic and literary influences, as Shoghi Effendi suggested. I don’t think the painting is limited to that; I think it is the enhancing of a created space where music and everything else can come out.

NLH: You made a film about your creative process in the Holy Land?

HCD: Some young film makers recorded several episodes of me painting and also talking about my work. It has not yet been finally edited.

NLH: Music and art naturally have elements in common, as well as differences. When I commissioned an artist to make the lid and soundboard paintings for my harpsichord many years ago, I was entranced to find out that, in the baroque view, art was not complete until the sound was made. Charles Wolcott observed that in music there are three protagonists involved: the creator or composer, the performer or interpreter, and the listener or public. In painting, there are two: the creator or artist and the public. In rare instances in contemporary music, such as John Cage’s 4’33’’ — a work of silence, in three movements! — the listener becomes the interpreter. Do you keep the public in mind when creating or do you prefer to convey an internal message?

HCD: I want to be faithful to the vision I have. When I get something that locks together and I feel satisfied, then I hope others will enjoy it. Perhaps they can access through it some of the energies that crystallized there. You know, I view art as, on the one hand, inspiration, and on the other, technique. We all borrow. We are all standing on the shoulders of the artists of the past. Don Rogers said to me early on: “Choose three different painters you like and fix yourself in the middle of them to start.” This is an interesting place to begin. You use a combination of their languages until you find your vision, combine them, and then go on from there to develop your own language and vision.

NLH: What three did you choose?

HCD: I didn’t do it. I had already gotten to the stage where I had a pretty independent idea of what I wanted to do, but there were those who influenced me, such as Don Rogers himself. I find the development of technique very exciting. One progressively acquires skills in the handling of materials. For example, the water color experience was a big help to me in handling acrylic, so that I was not hesitant to use acrylics in a more liquid form. In layering the work, in viscosity, in more liquid form, in solid painting with water spray — all quite exciting, quite revealing, textural stuff.

Untitled

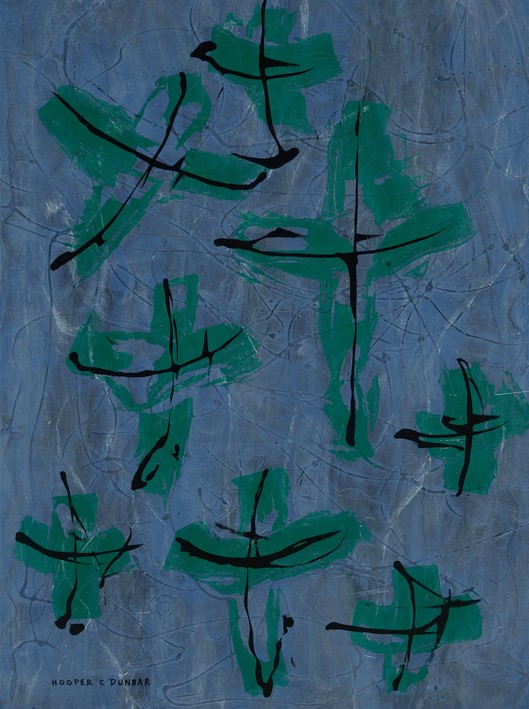

NLH: Do you ever refine or make adjustments after you finish?

HCD: Very seldom does that happen, but there can be a long time before a painting is finished. This fellow, for example . . . .

NLH: Is it called “The Block” or “I just don’t have time to get to it”?

HCD: Very seldom does that happen, but there can be a long time before a painting is finished. This fellow, for example . . . .

NLH: Is it called “The Block” or “I just don’t have time to get to it”?

Check This Out, 2012, Acrylic on Canvas, 40" x 30"

HCD: It’s not a block; it’s waiting for the right moment. I’m contemplating it. Some things are very simple. For a long time, I was not sure — see the blue one with crosses — that I was finished, but I am quite happy with it now that it is framed.

NLH: The Universal House of Justice, commenting on chaos and destructive forces in contemporary society, said: “Even music, art, and literature, which are to represent and inspire the noblest sentiments and highest aspirations and should be a source of comfort and tranquility for troubled souls have strayed from the straight path and are now the mirrors of the soiled hearts of this confused, unprincipled, and disordered age.”* Have you ever destroyed or disavowed a work after you have finished it?

HCD: Not from those motives. Sometimes the painting just doesn’t work, but I usually re-work my paintings, because they are layered. Sometimes they are obliterated in the process. Sometimes there are several levels before I find what satisfies me. I find that there is a lot of trash art out there. Some pieces seem based on physical stimulation or sensation, and, once you have had it and experienced it, then it burns out. It is like a firecracker. Once it explodes, there is nothing left. You are shocked by it. Shock of the new! I don’t know, I am not very attracted to that. In fact, I find it tedious that the art world is so occupied with pop and cartoon art and triviality. I don’t want to dwell on it negatively, but I see very few painters coming along who know what they want to do next.

NLH: It is certainly a reflection of the spiritual nature of humanity at this time, or the lack of it.

HCD: Yes, and so much of it is Americanized, art made to sell — art for a certain market. Fortunately, I don’t worry about that. I am relaxed enough that I can paint what I want. There are collectors interested in my work, which provide the means for me to buy more paint, more canvases, and to travel about to enjoy art in other countries. I find that traveling around you discover national artists, some very gifted people. There is so much out there — German, Danish, Finnish, Spanish — some wonderful artists.

NLH: Do you see a time when your work will evolve with new technologies?

HCD: No, I am happy to have a bit of the iridescent paints that have come out in the last decade or so, without them being fluorescent. I like their reflective qualities.

NLH: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said: “All Art is a gift of the Holy Spirit . . . These gifts are fulfilling their highest purpose, when showing forth the praise of God.”** Artists should be at the center of the Bahá’í community and should attract dynamics and spiritual forces to the community. Instead, they are often ignored, misunderstood, presented incorrectly. What are your counsels?

HCD: I think what you have just described is a reflection of the world in general. Some people are wealthy, while some of us have to keep our nose to the grindstones. I think that as the Bahá’í Faith grows art will become more center-stage. As art is a gift of the Holy Spirit, so thinking is a gift of the Holy Spirit. There was a woman who wrote to the Guardian, asking him to pray for her. She said that she gets into an ecstatic state and produces automatic writing and automatic painting. Shoghi Effendi said that he appreciated what she was trying to do, but cautioned her that this sounded more like a psychic practice than an artistic practice. Such art is actually an outcome of the mind, of thinking. An awakened mind, however, can reflect images of a higher realm. That may sound psychic, but it isn’t. It is not an automatic thing. It comes through the mind. If you watch any painter working, you will see them thinking, calculating, choosing, then balancing and counterbalancing until they have the harmonious result or a chaotic one, depending on what happens to be going on in their souls.

NLH: For the Spanish composer, Manuel de Falla, who was very religious, every composition had to be an evolution of his artistic being. He would not pour out popular works in order to earn money, yet ironically his work became very popular and very famous. Do your works relate to each other in this way, on a continuum? A spiral? A return? Transcendence?

HCD: In an interview I had in one of the galleries, a gentleman said to me: “You can’t seem to make up your mind what your style is. Make up your mind.” And I thanked him for his comment. I find that my work moves along four or five lines. In my own imagination, they enrich each other. There are symbols, circles, crosses, and then there are the calligraphic elements, the textural elements, and all of these come and go in the paintings and I see their roots as progressive. And gradually, as I get enough work out there, people say “I can’t pigeonhole what his art is like but I can see that it is a Dunbar.” And if you can get to that stage, then that is an achievement.

NLH: Do you ever work these artistic problems out in your dreams?

HCD: I do occasionally see things in a dream, but it is hard to get it from the dream to the canvas. Occasionally I see something that I have painted in a dream. We are told that there are these, what we could describe as angelic forces that sustain and inspire us, all unperceived by us.

NLH: That is the whole thing about art, isn’t it? That there is a continuum — that the pure souls from the other world inspire us here, serve as the leaven that leaveneth the world. To use Bahá’u’lláh’s own words: “The soul that hath remained faithful to the Cause of God, and stood unwaveringly firm in His Path shall, after his ascension, be possessed of such power that all the worlds which the Almighty hath created can benefit through him. Such a soul provideth, at the bidding of the Ideal King and Divine Educator, the pure leaven that leaveneth the world of being, and furnisheth the power through which the arts and wonders of the world are made manifest. Consider how meal needeth leaven to be leavened with. Those souls that are the symbols of detachment are the leaven of the world. Meditate on this, and be of the thankful.”*** Sometimes you find that artists get no recognition during their lifetime, only to have posthumous fame, such as in the case of American poet Emily Dickinson. What would you hope that your art would give to humanity and how would you like your art to be remembered?

HCD: I don’t have a lot of hope about that. There is a kind of resonance for people who are interested. The few artists and writers who have been members of the Universal Houses of Justice, such as David Ruhe, Douglas Martin, now myself, may be of historical interest in the future. Whether there will be enough of an opus to attract attention I can’t tell. It’s in the hands of the future.

NLH: If you had been painting today, then I would have asked you to do a rendering of Bahá’u’lláh’s prayer for midnight, with its references to the inner and outer senses.

HCD: I usually sleep through the midnight prayer. I used to paint a lot at night in the Holy Land. Now I have the daylight hours in which to do it. I like the light of the sun.

NLH: Is there anything else you would like to say or comment on?

HCD: To the degree that Bahá’í artists draw upon the influence of the Holy Spirit, along with past artists and the impact of nature, to the degree that they draw close to the vibrating power of Bahá’u’lláh’s words, this will get reflected in whatever artistic expression they produce. That influence is going to be understood and read by future generations because this is the common heritage we have. It will be interesting to see how Bahá’í art develops . . . if you think of the intense beauty and richness and magnitude of Islamic art, which is the most recent authentic expression of religious art, and how coherent it is with all its ceramics, pottery, calligraphy, it’s an astounding representation of the Holy Word — its architectural designs, its tile making, its miniature painting. All of it is completely coherent with the rest and you immediately recognize it as Islamic art. And I must say that with some of the Hindu art, you can see and feel this as well. So, it’s exciting to imagine what the character and homogeneity of the art deriving from the Most Great Revelation of God will be in the centuries to come and how much is latent within it, waiting to be released and to influence humanity in the future. It is quite extraordinary.

NLH: I do feel the Islamic influence in “Pulsing Icons,” the painting of yours I have in my home, as well as Pollock’s influence.

HCD: Islamic art derives from the same vibrating influence of the Word of God, its action on the mind, when one focuses on it to derive inspiration.

NLH: As a musician I have felt, often while practicing the piano, that through the vibrations made by the notes, an incredible channel for information opens up for me. Sometimes the information comes in such a strong way that I have to “turn it off,” for it is very distracting. Do you ever feel that you are a channel for art?

HCD: At our own level, that can happen to us. I think this even happened to Bahá’u’lláh. But this is not applicable to this time, to the people of this era. I think we are constrained only by how carefully we hone our techniques to become a clear, mirror-like reflection of the inspiration coming to us. And that takes years of experience. I have been doing this since 1988, some twenty-five years, and hope to do it for some several decades more.

NLH: Thank you, Hooper.

* — Compiler: Hornby, Helen Bassett. Lights of Guidance: A Bahá’í Reference File, 5th ed. New Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1997, 126-27.

** — Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1954, 167.

*** — Bahá’u’lláh, Translator: Shoghi Effendi, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, Section LXXXII, Para. 7.

NLH: The Universal House of Justice, commenting on chaos and destructive forces in contemporary society, said: “Even music, art, and literature, which are to represent and inspire the noblest sentiments and highest aspirations and should be a source of comfort and tranquility for troubled souls have strayed from the straight path and are now the mirrors of the soiled hearts of this confused, unprincipled, and disordered age.”* Have you ever destroyed or disavowed a work after you have finished it?

HCD: Not from those motives. Sometimes the painting just doesn’t work, but I usually re-work my paintings, because they are layered. Sometimes they are obliterated in the process. Sometimes there are several levels before I find what satisfies me. I find that there is a lot of trash art out there. Some pieces seem based on physical stimulation or sensation, and, once you have had it and experienced it, then it burns out. It is like a firecracker. Once it explodes, there is nothing left. You are shocked by it. Shock of the new! I don’t know, I am not very attracted to that. In fact, I find it tedious that the art world is so occupied with pop and cartoon art and triviality. I don’t want to dwell on it negatively, but I see very few painters coming along who know what they want to do next.

NLH: It is certainly a reflection of the spiritual nature of humanity at this time, or the lack of it.

HCD: Yes, and so much of it is Americanized, art made to sell — art for a certain market. Fortunately, I don’t worry about that. I am relaxed enough that I can paint what I want. There are collectors interested in my work, which provide the means for me to buy more paint, more canvases, and to travel about to enjoy art in other countries. I find that traveling around you discover national artists, some very gifted people. There is so much out there — German, Danish, Finnish, Spanish — some wonderful artists.

NLH: Do you see a time when your work will evolve with new technologies?

HCD: No, I am happy to have a bit of the iridescent paints that have come out in the last decade or so, without them being fluorescent. I like their reflective qualities.

NLH: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said: “All Art is a gift of the Holy Spirit . . . These gifts are fulfilling their highest purpose, when showing forth the praise of God.”** Artists should be at the center of the Bahá’í community and should attract dynamics and spiritual forces to the community. Instead, they are often ignored, misunderstood, presented incorrectly. What are your counsels?

HCD: I think what you have just described is a reflection of the world in general. Some people are wealthy, while some of us have to keep our nose to the grindstones. I think that as the Bahá’í Faith grows art will become more center-stage. As art is a gift of the Holy Spirit, so thinking is a gift of the Holy Spirit. There was a woman who wrote to the Guardian, asking him to pray for her. She said that she gets into an ecstatic state and produces automatic writing and automatic painting. Shoghi Effendi said that he appreciated what she was trying to do, but cautioned her that this sounded more like a psychic practice than an artistic practice. Such art is actually an outcome of the mind, of thinking. An awakened mind, however, can reflect images of a higher realm. That may sound psychic, but it isn’t. It is not an automatic thing. It comes through the mind. If you watch any painter working, you will see them thinking, calculating, choosing, then balancing and counterbalancing until they have the harmonious result or a chaotic one, depending on what happens to be going on in their souls.

NLH: For the Spanish composer, Manuel de Falla, who was very religious, every composition had to be an evolution of his artistic being. He would not pour out popular works in order to earn money, yet ironically his work became very popular and very famous. Do your works relate to each other in this way, on a continuum? A spiral? A return? Transcendence?

HCD: In an interview I had in one of the galleries, a gentleman said to me: “You can’t seem to make up your mind what your style is. Make up your mind.” And I thanked him for his comment. I find that my work moves along four or five lines. In my own imagination, they enrich each other. There are symbols, circles, crosses, and then there are the calligraphic elements, the textural elements, and all of these come and go in the paintings and I see their roots as progressive. And gradually, as I get enough work out there, people say “I can’t pigeonhole what his art is like but I can see that it is a Dunbar.” And if you can get to that stage, then that is an achievement.

NLH: Do you ever work these artistic problems out in your dreams?

HCD: I do occasionally see things in a dream, but it is hard to get it from the dream to the canvas. Occasionally I see something that I have painted in a dream. We are told that there are these, what we could describe as angelic forces that sustain and inspire us, all unperceived by us.

NLH: That is the whole thing about art, isn’t it? That there is a continuum — that the pure souls from the other world inspire us here, serve as the leaven that leaveneth the world. To use Bahá’u’lláh’s own words: “The soul that hath remained faithful to the Cause of God, and stood unwaveringly firm in His Path shall, after his ascension, be possessed of such power that all the worlds which the Almighty hath created can benefit through him. Such a soul provideth, at the bidding of the Ideal King and Divine Educator, the pure leaven that leaveneth the world of being, and furnisheth the power through which the arts and wonders of the world are made manifest. Consider how meal needeth leaven to be leavened with. Those souls that are the symbols of detachment are the leaven of the world. Meditate on this, and be of the thankful.”*** Sometimes you find that artists get no recognition during their lifetime, only to have posthumous fame, such as in the case of American poet Emily Dickinson. What would you hope that your art would give to humanity and how would you like your art to be remembered?

HCD: I don’t have a lot of hope about that. There is a kind of resonance for people who are interested. The few artists and writers who have been members of the Universal Houses of Justice, such as David Ruhe, Douglas Martin, now myself, may be of historical interest in the future. Whether there will be enough of an opus to attract attention I can’t tell. It’s in the hands of the future.

NLH: If you had been painting today, then I would have asked you to do a rendering of Bahá’u’lláh’s prayer for midnight, with its references to the inner and outer senses.

HCD: I usually sleep through the midnight prayer. I used to paint a lot at night in the Holy Land. Now I have the daylight hours in which to do it. I like the light of the sun.

NLH: Is there anything else you would like to say or comment on?

HCD: To the degree that Bahá’í artists draw upon the influence of the Holy Spirit, along with past artists and the impact of nature, to the degree that they draw close to the vibrating power of Bahá’u’lláh’s words, this will get reflected in whatever artistic expression they produce. That influence is going to be understood and read by future generations because this is the common heritage we have. It will be interesting to see how Bahá’í art develops . . . if you think of the intense beauty and richness and magnitude of Islamic art, which is the most recent authentic expression of religious art, and how coherent it is with all its ceramics, pottery, calligraphy, it’s an astounding representation of the Holy Word — its architectural designs, its tile making, its miniature painting. All of it is completely coherent with the rest and you immediately recognize it as Islamic art. And I must say that with some of the Hindu art, you can see and feel this as well. So, it’s exciting to imagine what the character and homogeneity of the art deriving from the Most Great Revelation of God will be in the centuries to come and how much is latent within it, waiting to be released and to influence humanity in the future. It is quite extraordinary.

NLH: I do feel the Islamic influence in “Pulsing Icons,” the painting of yours I have in my home, as well as Pollock’s influence.

HCD: Islamic art derives from the same vibrating influence of the Word of God, its action on the mind, when one focuses on it to derive inspiration.

NLH: As a musician I have felt, often while practicing the piano, that through the vibrations made by the notes, an incredible channel for information opens up for me. Sometimes the information comes in such a strong way that I have to “turn it off,” for it is very distracting. Do you ever feel that you are a channel for art?

HCD: At our own level, that can happen to us. I think this even happened to Bahá’u’lláh. But this is not applicable to this time, to the people of this era. I think we are constrained only by how carefully we hone our techniques to become a clear, mirror-like reflection of the inspiration coming to us. And that takes years of experience. I have been doing this since 1988, some twenty-five years, and hope to do it for some several decades more.

NLH: Thank you, Hooper.

* — Compiler: Hornby, Helen Bassett. Lights of Guidance: A Bahá’í Reference File, 5th ed. New Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1997, 126-27.

** — Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1954, 167.

*** — Bahá’u’lláh, Translator: Shoghi Effendi, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, Section LXXXII, Para. 7.

Nancy Lee Harper

Bio: Nancy Lee Harper became a Bahá’í in Austin, Texas in 1969. In 1975, she pioneered to Argentina with her husband and children, and later, in 1992, to Portugal. Dr. Harper served as head of piano studies at the Universidade de Aveiro in Portugal until 2013, when she retired and moved to Vancouver Island, B.C., to be close to family. A music educator who has performed and taught on four continents and in twenty-nine countries, including at the Juilliard School and the Eastman School of Music, Dr. Harper’s music may be heard on various outlets, including YouTube, iTunes, and Spotify. She is the author of a number of articles as books on such subjects such as Iberian music, piano pedagogy, and the relationship between music and medicine. In 2006, she was nominated for the Samii-Houseinpour Excellence in the Arts Prize. www.nancyleeharper.com