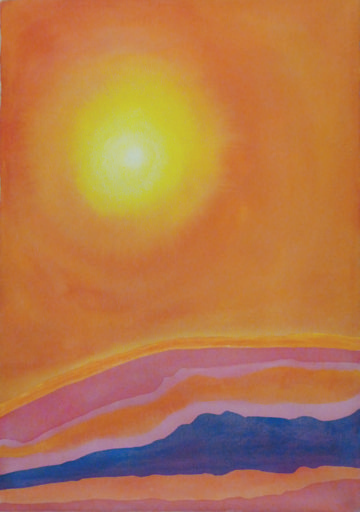

“Tropical Landscape” (1976) by Catharine McAvity

A Landscape Yearning Towards the Light:

A Year with the Paintings of Catharine McAvity

by SANDRA LYNN HUTCHISON

I. “THE COLOUR OF THE SEASONS”

The house stands on a lane that winds down to a river, the Kennebecasis — Mi’kmaq for “Little Long Bay Place” or “Little Snake.” The day I sign the lease marks exactly one year from the end of my treatment for a cancer my oncologist tells me I was lucky to survive. Maybe it was just luck, rather than the top notch medical treatment I received in Boston, but what matters are her parting words: “Once you get through this year, your chances are pretty good.” Now, as I stand in the living room in the falling light, I examine the world in which I will pass that year. I am surrounded by the paintings of New Brunswick artist Catharine McAvity, which hang on every wall, stand propped two or three deep along the walls in every hallway, and fill to capacity the third floor attic. Abstract images of flowers, trees, and celestial bodies burn brightly in the intense light of the setting sun. I am spellbound. The paintings conjure a world in which a dab of red paint can become a flower; a flower, a swimmeret; and the darkness of grief, the brilliant colors of unbounded joy. If there is a place where my odds of survival might increase, I believe it is here, among the paintings of Catharine McAvity.

It is not often that one has the chance to step inside, let alone inhabit, another artist’s vision. Yet that is what I will be doing this year, living and writing — about what I do not know yet — in a house filled with Catharine’s paintings, a house suitable, as the ad put it, for “a special person.” Catharine’s son John, who owns the house, plans to retire here one day. But for now he criss-crosses the globe for his work as a museum advocate. Although the “Artist’s House,” as John calls it, stands on a street in Rothesay, New Brunswick, it might be a dwelling artfully constructed on some newly discovered planet, one imagined by Catharine McAvity. As I move among its landscapes, I am transported, as Catharine must have been from the dark world in which she had to carry on living after she lost her only daughter in a car accident. Paddy would have been in her early twenties; Catharine would have been not much more than forty, just cresting middle age and riding a wave that might have carried her to new shores as she became more free from domestic responsibilities, but which plunged her, instead, into years of darkness marked by the decline of her husband’s mental health and the breakdown of her marriage. Then, in an effort to reclaim some happiness, after a 20 year hiatus, she took up painting again.

When I moved into the Artist’s House, John went next door to stay with his neighbor Sue, an old friend of his mother’s who used to push him in his pram, he tells me. But before he leaves for Ottawa, where he lives during the winter, he drops by the Artist’s House to see me. “A couple of things,” he says. “First, you might be interested in this.” He hands me an exhibition catalogue entitled The Colour of the Seasons / La Couleur des Saisons, written by curator Ian Lumsden to accompany a retrospective exhibition of Catharine’s paintings at the New Brunswick Museum in the fall of 2010. “Now, follow me,” John says, as he takes me around to meet my new neighbours on the lane. Most are old Canadian — Atlantic Canadian. I recognize in them the same quiet ways of my own people, who settled the land in southwestern Ontario, the same self-effacing manner but with a slight difference: these neighbors seem to be more open, more comfortable with words. Still, I can see by the formality with which they receive me — tea comes in china cups with saucers and is accompanied by a fine tray of bakery-made cookies — there will be no open door policy. Clearly, my neighbors are private people who like to keep to themselves.

As we sit and drink tea, I tell the neighbors I own a home in Maine, where my husband still holds the fort. I tell them I have come to try Canada again, with the idea of moving back to the country of my birth and bringing my American husband with me. They know my daughter will finish Grade 12 at a nearby school. I do not tell them I have come to write. And they do not know that I have been ill, very ill, and am lucky to be alive. I do not tell them that emerging from a serious illness is like coming up after being submerged too long underwater. You need to catch your breath. You need to get your bearings. You need to find your way to shore. My new neighbors laugh when I say I am relieved to have fled the hard, spare ways of my Yankee neighbors back in Maine. Like my United Empire Loyalist ancestors before me, I tell them, I have always known that only one direction leads to safety — north. And even though they laugh, I know this is something they understand.

II. AUTUMN

On September afternoons, I leave the paintings behind to take walks along the gravelly beaches that line the Kennebecasis, or to climb Allison Road to the top of what the locals call Telescope Hill. After long absence, Canada truly does seem, to me, a peaceable kingdom; and Rothesay, a green world to rival any of Shakespeare’s. My time here seems like some bucolic interlude, a chance to rest in a verdant meadow after a long and arduous journey up a steep mountain. As I reach the top of Telescope Hill, I almost expect to see a shepherd and his flock making their way through the green space below, but I see only trees burnt with sun, shedding their brilliant leaves in a whoosh of wild offshore wind. And beyond the green space and the roof tops, I can follow lean sapphire body of the Kennebecasis, alive with white sails, as it snakes through the valley. This landscape feeds my soul. If I were to take up writing poems again, I would find much material here.

Sometimes my daughter arrives home from school while I am out walking. We agree to keep extra keys for the house and for the car in the empty A&W root beer mug that sits on a shelf in the room next to the garage, a room Catharine once used as a studio. “The Red Cloud,” she called it, because of the woodstove that warmed it. I tell my daughter to use the house key to let herself in. She knows not to go out in the car alone. At 15, she has earned only a learner’s permit and needs to be with a licensed driver whenever she gets behind the wheel. In Maine, her driving practice has been limited to parking lots at the nearby university where I teach. But here, in Canada, she needs to branch out — to practice highway driving.

I am heartened by the fact that driving seems a tamer activity here in Canada. Is the feeling rooted in some prejudice I hold with respect to the country of my birth — a belief that everyone and everything is better somehow, safer, more reliable? Or is it that students do not dominate the roads in Rothesay as they do in our village in Maine, but rather middle aged women ferrying children to hockey or Tae Kwon Do, and family men heading to their jobs as bankers and brokers in the city? Maybe I have a false sense of security, but I do think the drivers in New Brunswick are more civilized — typical Canadians, courteous and retiring. More SUVs cruise the roads than pick-up trucks. And I don’t think I need to worry about pulling up behind a car from whose trunk dangles the head and paw of a slain black bear, as I once did on Maine’s I-95.

On Wednesday afternoons, when my daughter gets out of school early, we take to the roads so she can practice highway driving. On one particularly sunny day, we head east out of Rothesay and find ourselves cruising down the road to the seaside town of Saint Martins. Although Maine is home to some of the longest, sandiest stretches of beaches north of the Carolinas, we live inland, on the edge of a large stretch of caribou bog. Long ago, the sea covered these bog lands. A geologist friend once took me along when he drilled deep into the sediment with a coring device, through 40 layers of earth into history. When he let me touch the earth from the last section of the coring device, I felt a sense of awe and disbelief. How had the sea managed to retreat so far from us? From our village in Maine, a drive to the coast takes more than an hour, so for me, an afternoon by the sea, in Saint Martins or anywhere, is a special occasion akin to a celebration.

The road to Saint Martins is a narrow, winding one that wends its way past the airport, a swampy lake, a few small towns, each just a handful of houses really, and through endless coniferous forest. We drive along the pock-marked road for some time. My daughter is taking the road like a master, and instead of putting my foot on an imaginary brake, I am settling in and enjoying the ride. We make our way down the highway for a good 40 minutes before we see a sign telling us we have arrived. We crest a hill and see below us, in a valley framed by red sandstone cliffs, the town of Saint Martins, aglow in the mid-afternoon light. Beyond the cliffs, the sea stretches to an invisible horizon where it meets the sky. As I examine the view, I am overcome by a feeling of déjà vu. Where have I seen this scene before? And then it comes to me, “Look,” I say to my daughter, “we are driving into a painting by Catharine McAvity!”

We get out of the car to take a look. Below us lies a womb-like world of sea and sky — a wide cup of azure sea framed by strips of green and an expanse of mauve sky dotted with cumulous clouds so puffy you might imagine they are giant dandelion tufts set free by the wind. It is this very view, I feel sure, that inspired Catharine, in 1987, to paint “Saint Martins Vista.” In the years just before making this painting, Catharine had visited New York for the first time and viewed the work of major twentieth century American artists, such as Milton Avery. In this painting, the influence of Avery can be discerned in what curator Ian Lumsden describes as “decorative patterning.”

In “Saint Martins Vista,” Catharine still employs the wet-in-wet technique that advanced her work in the late 1960s, when she first encountered the colour stain painters through workshops led by painters such as Ken Lochhead at Sunbury Shores Art & Nature Centre in Saint Andrews. But in “Saint Martins Vista,” Catharine adds a painted edge, as if to emphasize that this is a work of art and it is her own version of the scene we are viewing. This painting speaks of a new development in her artistic vision. Now Catharine’s work shows that while she is attuned to the work of other painters, she is beginning to see the world through her own eyes. As I stand on the hill and look down on the scene, I, too, see it through Catharine’s eyes.

Without doubt, I reflect, this particular painting speaks of her arrival at the home Catharine clearly found in the world of landscape painting. In the roundness of the forms, in the sense of womb-like enclosure those forms evince, and in the decorative aspects of the composition, the painting communicates both a sense of liberation and a joyous feeling of arrival at a place of belonging. The landscape is fully abstracted, pared down to its essentials. What matters is form — the quintessential beauty. “The way I paint is the way I feel,” Catharine once said. “I get the essence of the subject then I try to simplify.” (1985)

We get back into the car and drive down the hill to the village of Saint Martins. We have imbibed beauty: now we need real food. Just off the main road, we discover the Coastal Tides restaurant, a place we will visit often during our sojourn in Rothesay — when we can find it open in the off season. To the surprise of the waitress, we order what will be our usual meal at this restaurant that specializes in fresh seafood: veggie burgers. At times like this, we are reminded that we hail from the ever-so-green state of Maine — the world of organic farms and back-to-the-landers, where in many circles vegetarians are not in the minority.

After we finish our meal at the Coastal Tides, we comb the beach for sea glass and shells. By the time we are ready to head home, dusk is falling. My daughter sets out along the winding road. But the driver of the truck behind us is impatient; he wants to pass. A few minutes later, he forges ahead, almost sideswiping us as he races by. Clearly, this driver knows his way, while we do not. And in the dark, the road before us seems longer than it did on the way here.

“Do you want to drive?” my daughter asks me.

“I would be happy to,” I say. We pull over to change places, and I ferry us safely home.

III. WINTER

In the months after I was diagnosed with cancer, I read medical articles online almost every day. My oncologist once joked that my husband and I had earned our M.D.’s. “But you lack clinical experience!” she warned us — not to mention basic training in anatomy, physiology, chemistry and biology. “You have come a long way,” she said, “but be careful of diagnosing yourself. You’re at that stage when people succumb to medical student syndrome. You’ll think you have every disease you read about!” She smiles at the curiousness of a syndrome that is, for her, safely located in the distant past. But we do not smile. We are suffering from this affliction. We have filled one whole standing file cabinet with the latest medical articles. We know if the studies are single institution studies or the more telling multi-institution studies completed over a number of years, with large samplings of patients that make for more reliable results. We are after the truth — the real truth about my cancer.

At my last visit, my oncologist ordered one more test — DNA sequencing to determine if there is a genetic basis for the cancer. As I wait by the phone for the results, I pick up The Colour of the Seasons from where it lies on the glass coffee table in the living room. As I leaf through its pages, I note that in 1971 Catharine produced a body of large scale work influenced by artists whose aesthetic was shaped by post-war American Abstract Expressionism. A reproduction of one of Catharine’s paintings along these lines, “Blue Genes,” catches my eye. It is not pure action painting by any means: clearly, the paint has not been hurled at the canvas as it was so famously by Jackson Pollock. But the dynamic chains of bold, primary colors that spill down the canvas, defying its edges with their explosive energy, inscribe Catharine’s debt to the aesthetic promulgated by this movement, especially its belief in the unimportance of the framing edge.

I can see how a painting such as “Blue Genes” represents a quantum leap forward for Catharine, who had, only a few years before, been preoccupied with creating conventional portraits of flowers placed at the centre of the canvas. But in this painting and others from these years, she is staining unprimed canvas with colour after the fashion of work she encountered in a 1966 exhibition — “frankenthaler noland olitski” — organized by the then new director of the New Brunswick Museum, the avant-garde Barry Lord, an American who came to Saint John in 1964. No doubt the image of the painting that appears in the catalogue, of a wild chain of blue genes highlighted by dark spots of purple and red coiling down either side of a large canvas, does not do justice to the actual painting. But the image does manage to communicate something of the elusive but omnipresent grand energy of the body and its cells — the powerful secrets of their invisible life.

Blue genes. Why blue? Sad genes? Yes, genes that carry secrets within themselves. Genes that have unwittingly betrayed the body. Genes gone AWOL. Sequences gone awry, auguring bodies gone to graves over which flowers, like the watercolour ones in Catharine’s early paintings, blow evasively in the wind. A gene within me or anybody else could go wild at any time, like a defiant teenager who grabs the keys and takes off in your car without your permission — who knows where? And like the same teenager, a gene could act out. It might just decide to defy the strict rules of the genetic code and do its own thing. And such an action might set into motion a grave illness.

In the strident imagery of a painting such as “Blue Genes,” the viewer senses Catharine’s newfound political awareness — the death of some innocence perhaps, or an end to contentment with domestic life, even anger at its confining power. And, perhaps most important to Catharine as an artist, a painting such as this embodies a powerful desire to move beyond of the conventional pictorial language so often employed by amateur women painters. I remember that it is 1971 when Catharine makes this painting. Second Wave Feminism is sweeping across the land. Along with it, a wave of protest against the Vietnam War, the spirit of which Barry Lord had brought with him to Saint John.

On Friday afternoon, the phone call comes. The results on my genetic testing: “indefinite,” but “probably not.” I decide to add “probably” and “indefinite” to a list of words I do not like to admit into my vocabulary — a list that includes the word “cancer.” Now I turn my attention back to an essay I have been writing, an academic piece on the use of poetry in the digital age. A slow art striving to find a place in lightning-fast times, does poetry have a future? Writing a paper on a subject like this is perhaps useful — a contribution to an important conversation that needs to take place. But the experience of cancer has given me a different perspective than the one I once had, not just on poetry by on all of life. I find myself struggling to engage with the central tenet of my own essay. Does everything we do have to have a purpose? Isn’t joy enough of a reason to do anything, including the practice of an art?

We have been living in the Artist’s House for four months now. School is closed for the Christmas holidays, and it is time to go home — if we can. A heavy snow has fallen, and the roads in New Brunswick are never ploughed as promptly as they are in Maine. Still, we begin to pack. We plan to set out for Maine first thing in the morning. Then, just as we are placing our sweaters, wool socks and flannel pyjamas in suitcases, the lights go out. I look out the window. Sleet pelts the glass so hard it makes a pinging sound. Though dusk is falling, the streetlamps do not glow; nor does any other light in any other house along the lane. Clearly, the power has gone out. By evening, we are caught in the midst of a violent ice storm — one of the worst in the history of the region, we find out later. We have no choice but to postpone our departure and wait for the storm to subside.

Two days later, we still huddle in front of the fire place. We are burning the wood John told us was off limits — but that was when we had other sources of heat. The fireplace, we discover when we remove the large board John placed inside the screen before he left, lets in almost as much cold air as the fire gives off heat. For the past two nights, we have wrapped ourselves in as many blankets as we can find and slept on a sofa pulled up close to the fire. Last night we added John’s very old, very thick Hudson’s Bay blanket — the best defense, we discovered, against the cold. When I cannot sleep for the bitter cold that creeps into my bones, I pass the time communing with the paintings that hang on the living room walls — or trying to. But in the inconstant light of the flickering flames, they remain mute. I remember that their colours come alive in the hours closest to dawn and to dusk, when natural light is most intense. Catharine’s paintings, you might say, live in the light.

Any driver who lives in a place where winter lasts almost half the year knows that, at one time or another, you have to venture out on roads slick with ice. But the current road conditions are ones even the most experienced of drivers should not brave. Still, our hands and feet ache with the cold so we lock up the house and set out, with me in the driver’s seat as our car crawls along Rothesay Road. Usually the scene of much jovial activity, the colorful ice huts on the river stand abandoned, their bright hues muted by ice and snow. All the way to the border and on into Maine, we are met by a landscape in hibernation — white on white, with perhaps the faintest shades of grey or blue.

This is the same colour scheme Catharine used in the snowscapes of the “Hibernal” series she painted in the early 1980s, almost a decade after her marriage to Dr. Jack Oughton, the retired zoology professor she met when he served as director at Sunbury Shores. Paintings such as “Hibernal V” (1981), which hangs on a wall at a turn in the stairs in the Artist’s House, portray minimalist landscapes. This particular painting evokes a horizon rendered in three blurry, wavering lines of dark blue, magenta, and mauve paint that stretch across two canvases. Painted the same year, “Hibernal II” is even more spare.

As we crawl down Highway 9, passing snow-laden branches caught in the brilliant rigor mortis of ice, it occurs to me that this is just the kind of scene Jack Oughton might like to photograph. I recall reading about the sequences of slides he routinely took and carefully labelled, and I think about how they must have helped Catharine see subtle differences not just in form but in colour. To the untrained eye, all snowscapes may look the same, but for a painter such as Catharine, what subtle hues might be discovered in a snowbound landscape like this one? Colour — as a painter, Catharine understood its power. But from the “Hibernal” series, it seems clear that, as a human being, she understood that as we move through life’s seasons, from birth to death, we cannot always live in brilliant colour.

IV. SPRING

Spring erupts in Rothesay with massive flooding. Sue’s house is ravaged, but John’s remains untouched. On April afternoons, when Sue must supervise the workmen who are refinishing the floor in her parlor, I set out on long walks. Now that the sidewalks are clear of ice, the runners are out in full force. Bevies of women dressed in skin tight black leggings and matching jackets, with water bottles clasped to their waists, command the sidewalks. while older couples, with their glossy-haired dogs, cling to the patches of grass that line them. Everyone comes out of hibernation, and for me life gets busy with a round of social engagements. There’s a symphony concert to attend and a Mother’s Day brunch to enjoy. And the piece de resistance: a community art show. Each year, painters come from all over New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to show their work at this fundraiser. In a community comprised not only of art lovers but of serious art collectors, the spring art show is one of the highpoints of the year.

Just as in past years, this art show is spectacular. But for me, buying one of the paintings in the art show would be tantamount to a betrayal. For six months now I have lived amidst a massive collection of paintings that together map a world. To enter the world of another painter would mean turning my back on Catharine’s paintings. And I have come to feel at home in Catharine’s world and do not want to leave it. I wonder why Catharine’s paintings will not be shown alongside those of these living artists? Perhaps, like creatures who have adapted to their natural habitat, they do best in the Artist’s House, a place with its own eco system — one in which form and colour and light work together to create a perfect balance of elements.

Over the months, I have learned that the Artist’s House is far from perfect. As is the case in many old houses, there is hardly any cupboard space, the laundry is in the basement, and the one bathroom is located, inconveniently, upstairs. The old radiators hiss and rumble. The garage is too small for my car, unless I move all the ladders and lawn equipment into Catharine’s studio, which I do. And sharing a circular driveway with a next door neighbor requires a great deal of cooperation as well as planning. But these are mere details, minor inconveniences. What matters is that I am six months closer to health. For now, I have abandoned my essay on poetry in the hope that a more engaging writing project will come my way.

“Stay calm and go for gold” — I read the words on the mug I drink my tea from each morning, and I remind myself that passing time is a beloved friend to anyone living with a cancer diagnosis. Each day, each month without symptoms brings you closer to the prize. For a long time I imagined John was awarded this mug at some grand sailing event — until I discovered its twin on a shelf at the local Walmart. Good health, I think to myself, might seem a little like that to some people: something so easily obtained it seems of little value. But for the cancer patient moving through the post treatment months, good health is a much coveted though unexpected prize — like a set of paintings that come into one’s life quite unexpectedly.

As the days of spring pass, a fresh rain of emails from John falls onto the screen of my computer. He has gone to Hong Kong for business and found time to be fitted for a suit by the former colony’s legendary tailors. He is in Zurich for a meeting and consuming some very dark and delicious Swiss chocolate. He asks if we have a move out day, and I am reminded that it will not be long before I have to leave the Artist’s House and return home to Maine — if I can call my adopted state “home.” I continue to wonder if it is here, in Canada, I belong. I continue to search for my next writing project. Now that the ice and snow is finally gone from the roads, my daughter and I take up, once again, our Wednesday drives to Saint Martins, stopping for dinner at the Coastal Tides, followed by a long walk on the beach in the welcome light of the lengthening days.

One spring evening, after I have returned from a hike up Telescope Hill, I find a note on the kitchen table. My daughter, who has now passed her driver’s test, says she tried to call me twice but I did not answer. I look at my cell phone. Yes, somehow the ringer got turned off and there are the two unanswered calls. A math study group has been formed to review the material to be covered in the final exam, she writes in the note. She needs to join the group, though she doesn’t say where it meets or for how long. She aced her driver’s test, and I know I shouldn’t worry. But when I see that it is growing dark and a light rain has begun to fall, I do. The roads will be slick in those first few minutes, I think to myself. Then I realize I am powerless. I can do nothing, so I pace the halls, pace and stop in front of two paintings Catharine completed in 1975 — “Aura I” and “Luna II.”

It was in this year — 1975 — that Catharine and Jack began to spend winters on St. Vincent in the Grenadines. As a result of these travels, a new kind of light enters the paintings. There is a new approach to form and a fresh understanding of the spirit of form. According to Ian Lumsden, these paintings and others done in 1975 show the influence of Adolph Gottlieb’s “Burst” series. Now Catharine places rounded, luminous shapes strategically on the canvas, to evoke celestial bodies — the sun and the moon. The result is poetic, visionary landscapes in the spirit of the Lyrical Abstractionists. In these two paintings, and in others such as “Field Shapes” (1978), which hangs in the living room of the Artist’s House, Catharine has found a way to infuse colour with light. As I look at them, it occurs to me that these paintings are not just studies in light, but also exercises in the practice of happiness.

Tonight, however, the happy colours of these paintings irritate me. In the stark light of the adjustable reading lamp I have turned up high so I can pass the time reading a novel, the colours burn too brightly — as if it were midday. How dare Catharine’s paintings assert the possibility of choosing joy, happiness, and light in the middle of this dark, rainy night when my daughter is out in the car who knows where and I am worried sick? I ask myself again how Catharine could have discovered beauty — the essential form of the landscape and its luminous colours — in the face of personal tragedy?

I realize something I have not understood before: in all the months I have lived in the Artist’s House, Catharine’s paintings have spoken to me, but I have not answered them. How should I answer? Catharine had lost a child, her only daughter, who stood at the beginning of her life. Yet she had learned to live in luminous colour. As a painter, Catharine found what lay behind the particulars of experience: the edifying, coherent structure. She saw the essential form of things, their colour, their hidden light. Surely, it was a habit anyone could master — the habit of seeing and living in the light? Finally, after much anguished waiting, I decide to go to bed. When I get up the next morning, I see that the car is in the driveway and my daughter is safely asleep in her bed.

V. SUMMER

June 1st — only three more weeks until the end of the school year. But before it is all over, there will be various rites of passage: exams; a graduation ceremony; and the prom, that penultimate rite of passage for the teenage soul, which, at this school, takes the form of a coming out ball in the grand old southern sense of the term, complete with spotlighted introductions of each couple as it enters the large cafeteria-turned-ballroom and poses for photos. Today, my daughter has driven to school and is late coming home. Sometimes, these days, I feel as if I am the teenager and she is the owner of my new Subaru. I am waiting for her to get home so I can drive to my evening yoga class. I am practicing yoga because my oncologist has recommended it. Other cancer survivors tell me it is a good way to manage the anxiety that follows a diagnosis, even if one has passed through cancer treatment with flying colours and has been declared, for the time being, cancer free.

I listen for the sound of tires rolling down the lane and onto the gravel driveway. But I hear nothing. I look out the window. Now the days grow longer; and when the light leaves the sky, it does so more slowly than on spring afternoons, as if taking care not to disturb anyone who watches. Usually, I savor the hour between day and night. I like to watch the sun sink by degrees until it disappears beneath the horizon, but tonight I close my eyes as I lie on the creaky old queen-sized bed in my bedroom and practice the meditation techniques I learned in my yoga classes. I concentrate on the breath. Still, I can’t help listening for the sound of an engine or the slamming of a car door. But what I hear, instead, is the hooting of an owl.

On this June night, just weeks before the summer solstice, the air turns surprisingly cold and the wind rushes through the cedars with the power of a thousand wings sweeping through the sky, though I know of only one owl. I turn off the light and look out the window. A throng of cumulous clouds clears the face of the rising moon. Suddenly, moonlight floods the room, falling in full force on “Aestival,” the painting by Catharine that hangs opposite my bed. A visionary summer landscape opens up before me. Even on a cool night like this one in early June, the bright pastel colours warm the room with an almost carnival-like show of light. Before long, I fall asleep in their warm blaze. When I wake up a few hours later, the yoga class I was supposed to attend is long over and my daughter is sitting at her desk burning the midnight oil.

Catharine painted “Aestival” in 1985, less than a decade after her first trip to Europe in 1977, at the age of 62. That year she and Jack spent the winter in Provence, where she viewed the work of masters such as Cezanne, Van Gogh, and Matisse, painters who were drawn to the lucid beauty of the sere Provencal landscape. I recall a French project with which I helped my daughter when she was in middle school, a poster on which we glued images cut from magazines to evoke a picture of life in that light-filled province. While working on the project, I learned that the light is different in Provence, clearer and brighter, because of mistrals — strong, cold north-easterly winds that blow through southern France, mainly in winter, clearing away the dust so that you can see for miles.

I wonder what could have brought such light into Catharine’s paintings? A winter in Provence? And I ask myself how can such alchemy be achieved not just in paintings, but in life? How can a landscape or a life be transformed into a thing of beauty? What is form anyway? What is colour? What is light — really? Could the term “form” also be used to describe the shape of a life, its narrative? And what is colour and light but hope? Catharine’s paintings, I begin to understand, are studies in hope.

Light — in Catharine’s paintings, I begin to see, grief is translated into the poetry of light. In much of her mature work, it floods the canvas. And what is light, after all, but the absence of darkness? What is the decision to choose happiness in the wake of pain except the determination to wear a mask to cover one’s sorrow in the hope of changing, over time, the resigned face of heartbreak into the radiant face of acquiescence?

The summer solstice comes and goes, and, with it, the series of rites that mark my daughter’s transition from the dependence that comes from living at home with one’s parents to the autonomy of living on a university campus. Come fall, she will strike out on her own path. Once the ceremonies and celebrations have ended, we pack up our things and prepare to leave Rothesay. It will be hard to leave the Artist’s House, even its small cupboards, its downstairs laundry, its single bathroom, and the field mouse which took refuge in the basement after the great spring floods. It will be hard to leave because leaving will mean stepping outside Catharine’s world and saying goodbye to her paintings.

As we pull out of the driveway the last time, my daughter is in the driver’s seat. I turn to look at her. She drives with confidence, her newly acquired driver’s license tucked securely in the pocket of her wallet, which sits propped up in the cup holder. Her long blonde hair streams down her back. Her eyes are fixed on the road ahead. She does not look back, as I do, with yearning at the Artist’s House. I force myself to look ahead too. I can now count nine months post treatment. It is looking good.

Before we know it, we have crossed the border and are cruising down Highway 9, the Airline, as it is called, through the hills of northern Maine — a landscape that sparkles with blue lakes rife with bass and rivers that still run with salmon. In the clear bright light of the June day, our trip feels like some Sunday drive we have decided to take without a destination in mind. We consider stopping at a restaurant we know that serves delicious food, a restaurant whose name I always get wrong.

“Is it ‘Hole in the Wall’?”

“No, ‘Nook and Cranny’!”

But we decide to press on. I breathe a sigh of relief at the halfway point on the route, marked by the defunct Cloud Nine Motel. I am looking forward to passing a glorious summer in our corner of Maine, a place we know so well we can, if we want to, find a different river, mountain, lake or coastal beach to visit every single day. As we make our way along the Airline, the sun’s rays almost blind us. The air is clear; the light, intense. But I am sure my daughter can handle the glare. With her in the driver’s seat, I am confident we will make it safely home. The last time we took this road together, months ago, at Christmas, the land lay covered in ice and snow. But now, in the intense light of late afternoon, we might be driving along a highway in Provence. When the car reaches the top of the highest hill along the route, we can see for miles.

It is sometimes said, often by those not involved in the making of it, that genuine art is born of great suffering. Such a remark is usually made in a spirit of blithe unawareness on the part of someone who is not a painter, not a writer, not an artist of any kind — someone who does not know anything about such mythical great suffering. In the voice of the one who makes such a remark, you can hear an undertone of relief that has its origins, I suspect, in the belief that such suffering is the lot of artists — those gifted with the ability to make beauty out of pain. The people who make such comments believe that such a vocation is for someone else, not them.

And so it might have been for Rothesay painter Catharine McAvity, who was born in 1915 and lived for the better part of the twentieth century. To create beautiful art made from great suffering was not a vocation she — or anyone — would choose. But once it was thrust upon her, she did not refuse it. Instead, she spent years seeking a form that might enable her to face and then transcend her suffering. In her painting, she chose to embrace the joy of the creative act and to travel towards the light, even amidst the darkness of personal tragedy.

After almost a year in the Artist’s House, I have come to believe that though art, be it great or good or mediocre, is often born of suffering, it does not have to choose that suffering as its subject. In fact, quite the opposite. The paintings of Catharine McAvity do not speak of their dark origins, but rather map a process of forgetting about them. For a while, Catharine’s life unfolded in the way that the lives of respectable women of a certain social standing in her generation were destined to unfold: she attended university to study secretarial science, even though art had long been her passion. She met and married a young man from a good family. She bore two children and began her life as a mother, wife, and socialite.

Fast forward 20 years: Catharine’s beloved daughter, newly married and with her whole life before her, loses her life in a car accident. At 42, Catharine’s life, as she once knew it, is over. It takes more than a decade for Catharine to find a voice for her grief in painting. Not until the late 1960s does her work begin to emerge on the New Brunswick art scene. She learns how to translate her grief into art. But who would guess that her newfound language would be colour and light?

In the writings of saints and mystics from diverse traditions, the burning away of self is often likened to a purifying fire, and suffering viewed as a kind of calamity that, if embraced, can become purely providential — a gift, a sweeping away of the old self, of what is unnecessary, extraneous, dysfunctional, so a new self can take shape. A demanding exercise in detachment whose fruit is the knowledge of what is needed to live happily and well. As far as I know, Catharine did not have a religious faith; nevertheless, her paintings speak of a deep communion with some source of joy and light.

By the time I take my daughter to university in the fall, a full year has passed. I am still here. And “here” is not Rothesay and not our village in Maine: it is anywhere I can manage to live in colour. I no longer know where “home” is, but I do know I must write about the paintings of Catharine McAvity. Lately, I have come to think it doesn’t matter if my home stands near a coast, is nestled on a rocky shore, sits in the middle of a pasture, or lies in the middle of a bog. I don’t know where I will end up, but I suppose if I were to choose some final destination, it would be a place with a river running through it, for rivers represent long life — a little long place where a river makes a bay and promises an ocean, a place where I can live in colour in a landscape yearning towards the light.