Editorial: Pandemics, Pandemonium, and Prayer

In this time of global crisis, one can hardly write an editorial — or think a thought, for that matter — that does not include the word “pandemic.” As many of us move into our second month of lockdown, the days before compulsory face masks and social distancing begin to recede into what seems, increasingly, like a long ago time, a time of foolish innocence when we gave little thought to the consequences of our everyday social interactions. Poets walked well peopled streets in search of inspiration; fiction writers headed to the library to research their latest story idea; memoirists combed through archives to learn more about their family history. And many of us, whether poet, prose writer, or painter, wended our way to coffee shops — for a solitary latte, to meet a friend, or just to get out of the house in the hope that a fresh environment would offer a fresh perspective.

Now all that is gone — the rhythm of moving from the inside to the outside is no more. Not only writers but much of the world is living inside and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. In embracing this new pattern of life, the artist has an edge. Inside is where those who make art have always lived, not just in the physical sense, as in the home or office, but also in the psychic sense, as in “inside” their own minds, memories, and imaginations. In order to create, the artist must inhabit the world within, a world that, depending on the individual mind or imagination, can be luminous with joy or as dark as a starless night.

Which brings me to “pandemonium” — the second and third meanings of the word. The proper noun “Pandemonium” refers to the capital of Hell in Milton’s great epic poem about the fall of Adam and Eve, Paradise Lost. Without the capital letter, the word is still a noun and refers in a more general way to the infernal regions — in other words, “hell,” lower case. Have we, like Milton’s fallen angel, Lucifer, descended into hell? Are these the “end times”? Has the wrath of God descended upon us? Are we — and I am talking about the whole world here — now inhabiting, in a real physical sense, a place that has long been viewed by many as a place of myth, a mere metaphor?

Shall we, then, consider the word “purgation” as well? It’s an unfashionable word in a time when the concept of sin is anachronism and the existence of a God has been called into question. But perhaps it is not God who is doing this to us, to the world? Perhaps it is we ourselves who are responsible? Could it be that it is time for human beings to rethink their relationship to one another? Perhaps this most chastening battle with the coronavirus offers us an opportunity to become more keenly aware of a truth: we are inextricably connected, one human family in which the fate of one affects the fate of all.

As Bahá’u’lláh wrote more than a century ago: “Ye are the fruits of one tree, and the leaves of one branch. Deal ye one with another with the utmost love and harmony, with friendliness and fellowship....So powerful is the light of unity that it can illuminate the whole earth.”(Gleanings, CXXXII) Elsewhere, He asserts: “O well-beloved ones! The tabernacle of unity hath been raised; regard ye not one another as strangers.” (The Tabernacle of Unity) To embody this truth in our daily lives means to do our utmost to care for one another, not just during this time of pandemic but once the threat of the virus has passed, by building communities of compassion, communities of souls who will not rest until all the people of the world no longer want for clean air, clean water, food, shelter, medical care — and love.

Perhaps it is time for prayerful consideration of the meaning of this world encircling crisis in which we, as a human race, find ourselves. Our time “inside” can become a time for reflection — which brings me to late April and early May of 1863 when Bahá’u’lláh spent twelve days “inside” a garden. The Najibiyyih garden in Baghdad lies across the river from the city; and it was to this garden that Bahá’u’lláh withdrew to prepare for the final leg of His journey of exile — to the prison city of Akka.

During the days He spent in the garden, Bahá’u’lláh was anticipating His imminent journey by sea to the most heinous of prison colonies in the Ottoman Empire, a place legendary for the foul smell of its air. How did He prepare for such a journey? Not by lamenting the harshness of His fate, or by railing against an unjust decree; rather, He spent His days walking amongst the roses, whispering to the nightingales, receiving an unending stream of well wishers — and making known, to a small handful of His followers, His station as the new Manifestation of God for this Day.

The historian Nabil tells this story:

“One night, the ninth night of the waxing moon, I happened to be one of those who watched beside His blessed tent. As the hour of midnight approached, I saw Him issue from His tent, pass by the places where some of His companions were sleeping, and begin to pace up and down the moonlit, flower-bordered avenues of the garden. So loud was the singing of the nightingales on every side that only those who were near Him could hear distinctly His voice. He continued to walk until, pausing in the midst of one of these avenues, He observed: ‘Consider these nightingales. So great is their love for these roses, that sleepless from dusk till dawn, they warble their melodies and commune with burning passion with the object of their adoration. How then can those who claim to be afire with the rose-like beauty of the Beloved choose to sleep?’ For three successive nights I watched and circled round His blessed tent. Every time I passed by the couch whereon He lay, I would find Him wakeful....”

(God Passes By, 153)

During this Ridvan season, we, at e*lix*ir, strive to remain wakeful. In this issue, we continue our mission to inspire, transform, and uplift our communities by presenting art of consequence and also relevance to our times. In this issue, we are pleased to offer a selection of poems by Andreana Lefton, drawn from a sequence that tells the story of Lida, a young Bahá’í who flees religious persecution in Iran; in the poems, we follow Lida’s treacherous journey from Tehran to a refugee camp in Turkey and, finally, to the United States. And in “The Writing Life” section of this issue, we present a prose piece by the same author. In “Bodies of Water,” Andreana Lefton probes the sources of creative inspiration, dowsing the landscape of imagination in search of such bodies of water as will nourish spirit.

In the memoir section, we offer Elizabeth M. Green’s “An Invisible Wave,” a firsthand account of a key event of the Civil Rights Movement in America, the Woolworth’s sit-in in Jackson, Mississippi, an event that sent Green a lifelong journey to uncover the sources of racism and to root them out, not only in the wider world but also within herself.

Those of us who practice the art of poetry sometimes find it instructive to examine the work of poets we admire, to see how they do what they do and to learn some secrets of the craft. To this end, we include, in the essay section, my own brief remarks on the art of Jane Kenyon in “Quiet Hours: The Luminous Particular in the Poetry of Jane Kenyon.”

In the “Voices of Iran” section, Tanin Azadi offers her reflections on Secret of Divine Civilization, a social treatise ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed to Iranian leaders and thinkers of His day. At this time of desperate social and economic crisis in Iran, what could be more instructive than His guidance regarding how material and spiritual prosperity might be achieved in modern day Iran?

Also from Iran comes the fourth installment of Eira’s comic, Ruhi & Riaz, which focuses our attention on an issue of great relevance to the Bahá’ís of that country: the newly mandated identity card. Merging humor with serious social commentary, in this installment of Ruhi & Riaz Eira carries forward her mission to keep western readers abreast of the challenges faced by Bahá’í youth in Iran today.

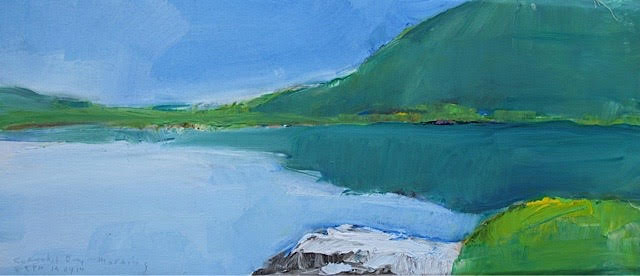

In the art section, we feature the paintings of Edward Epp, whose work invites us to ponder the haunting beauty of the landscape of the Pacific Northwest coast, specifically of British Columbia. Epp forges such a genuine marriage of art and spirit that when viewing his paintings, we may feel as if we are entering a place of prayer.

In “Looking Back on Books,” Allison Grover Khoury brings us up to date on books for Bahá’í children and their friends.

Last but not least, we present a Personal Reflection Piece by Kathryn Barlow, who in her commentary on the Ridvan tablet, brings alive the joy of those glorious twelve days Bahá’u’lláh passed in the Najibiyyih Garden, days of bliss during which his followers lay sleepless, intoxicated by His Presence.

In this time of pandemic, when we sometimes feel we are trapped in the infernal regions of pandemonium, let us remember Bahá’u’lláh’s call to humanity to become one people — to live and move as a single indivisible soul. And let us be mindful of our purpose as artists: to bear witness to the radiance of the spirit at a time of hellish darkness.

In response to this chastening pandemic, let us continue to envision the transformation of our communities and seek new ways to celebrate God’s remarkable creation. It is a time for us to engage ever more deeply in the miracle of transformation — our own and that of the entire human community. And so, in the spirit of the Ridvan season, let us enter into Najibiyyih Garden with Bahá’u’lláh — and rejoice.

— SLH