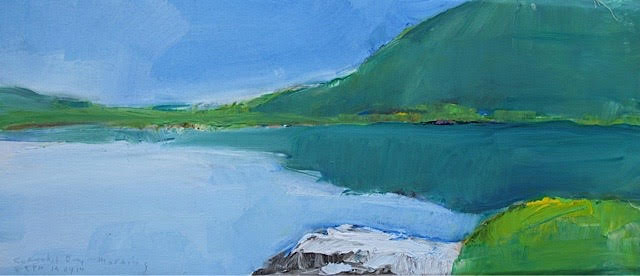

Cowachin Bay, oil on canvas, by Edward Epp, 2013

Bodies of Water: One Writer’s Practice

ANDRÉANA E. LEFTON

“Listen, you said, hear something new.

It’s the ocean calling you.”

— Jessica Barksdale

In London, by the Thames, I learned to walk fast, shoulders aslant, tilted headlong into the wind, the mist, the world. I’ve run by the Mediterranean, avoiding cigarette butts and looking for seaglass as my legs lifted off the land. Long, nighttime strolls by the Danube, up to the Fisherman’s Bastion in Budapest, everything blue and gold and magic. Walks and talks with my father, by the Potomac, or out at Great Falls, where grief over my mother’s death found an outlet in the relentless, pounding rush. Sunset power walks by Lake Michigan, after long days serving at the Bahá’í House of Worship, which I could still glimpse from the shoreline from where it stood, like a white mountain, watching.

And now, here I am, pacing the bridges of the Tennessee River, as I begin to heal and strengthen again. It’s twilight. A bird chirps in a crepe myrtle tree, and the sky is clear — the color of winter turning to spring. A bright claw — the crescent moon — digs day into night. The jittery human noises of a Saturday evening, plus complaining squirrels, chatter all around me.

When writers share their process, they usually speak of a daily routine of some kind. “I wake up at six and write for four hours,” is one piece of advice I’ve heard, but it does not resonate with me. I prefer the word practice. Doctors have practices. Yogis have practices. And as I writer, I am forging a practice too.

Part of my practice is practical: making money through my words, for a writer must earn her rice too. But for the most part, my practice is learning to embody my voice. For too many years, I felt shattered, too acutely aware of the pain of this world, and determined, somehow, to flee.

My embodied voice.

She knows how to enunciate, and commune. She’s the one who sits in silence behind the choir as they belt out Beethoven’s Ninth, listening in love and wonder to the music. She prays and acts, standing alongside the circle of women, who raise their arms against violence, for justice.

My voice is strict. She is disciplined and can hold her breath a long, long time. But when she finally breaks free from anxiety and self-control, she plunges into the darkness, seeking the treasure, the flame that can never be put out.

Poetry is my way of throwing a hook into life’s waters, watching the ripples go out from my words, and being amazed when I draw up some seaweed, or a torn map. Some clue to help me find my way through this wilderness. No fish is harmed by my poems. I lower down crumbs to feed the gentle ones.

For me, walking and writing, moving and thinking, go hand in hand. I try to walk five miles a day, though it can be three or seven. It helps that I don’t own a car right now. When I moved to Europe in 2010 for school and work, my father sold my silver Mazda 3, which I was more attached to than I care to admit. I’m back in the States now, in a place with a rhythmic name: Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Water, like walking, has been a constant in my writing practice. Water and trees and quiet. If I have those three elements, I can function. Flow. Currently, quiet is hard to come by. The world’s pulse is frenetic, and I’m a person who can feel sound-and-spirit waves, shaking my cells and dive-bombing my synapses.

Sirens, thumping music, barking dogs and creaking floors. Refugee crises, forest fires, worrisome viruses. Noises small and big jackhammer my brain and my practice falters, stumbles, misses a step.

On noisy days — by which I mean external or internal noisiness, days when other voices crowd in, and I feel put upon, restless, hard on myself — I fuss and complain, call a friend, say some prayers, get some sleep, and try to begin again. Or else I’m up at 3 am, scribbling, worrying. Watching videos. Listening to music. Which are all part of my practice too.

As my word count reaches and exceeds its limit, I want to give you something, some gem you can lift off this page and take with you on your walks, or hold onto, in your worried moments.

But the gem is already in you. As a poet and writer, all you need to do is reach out and stir your waters a little. Calm and disquiet yourself. Reflect and refract that secret pearl, buried beneath the silt and the seaweed.

Andréana E. Lefton