Editorial: Weaving the Threads

“O Lord! I sense the fragrance of Thy garment. Methinks Thou art near...” — so Mount Sinai cries out in Bahá’u’lláh’s Lawḥ-i-Aqdas. Throughout the Bahá’í Writings, imagery of clothing — garments, robes, and vestures — is invoked to symbolize divine realities and spiritual assurance. In The Kitáb-i-Íqán, for example, Bahá’u’lláh tells us to “divest” our bodies and souls of “the old garment” and to “array” ourselves with “the new and imperishable attire,” and in His The Surih of the Pen, He enjoins us to adorn our souls with “the silken vesture of certitude” and our bodies with “the broidered robe of the All-Merciful.”

How are we to respond to this invitation? During the past ten years, how have we, at e*lix*ir, adorned ourselves? What fabric have we woven? As we have passed through two bicentenaries, a special year dedicated to reflection on the life and work of the Master, a global pandemic, an uprising in Iran, and a period of marked escalation in global conflicts, what have we done to adorn the body of art that, as Shoghi Effendi explains, has been brought into being by the breaths of the holy spirit so bountifully wafted over creation by the new, the potent, the ultimately irresistible revelation of Bahá’u’lláh?

This special tenth anniversary issue of e*lix*ir is devoted to examining that fabric, looking at it from different angles — close up and from afar — to see what we can see, to attempt to form some idea about the emerging arts as they present themselves in these very early, very formative years of the Bahá’í dispensation.

Let us go back to the beginning: e*lix*ir came into being “... to showcase the work of artists who find inspiration in the Bahá’í revelation and to foster an aesthetic whose key ingredient is the conviction that the mission of art is to inspire, transform, and uplift individuals and communities.” The journal dedicated itself to becoming a refuge for the spirit, a site of experimentation in which both tradition and innovation had a place. It viewed art as a powerful instrument of individual and social transformation — an elixir that could change the dross of human experience from copper into gold — and saw artists as agents of social change who work at the intersection of the spiritual and material worlds but belong at the heart of the community.

How do artists effect change? How could they not when they share their spiritual bounty in work that uplifts our souls and awakens us to the possibility of living more purposeful lives? Such art mirrors who we are and gives us space to imagine who we want to become. Without doubt, the work published in e*lix*ir over the past ten years proclaims the truth that art lies at the heart of the processes of personal and social transformation, healing us with its loving hands — a metaphorical touching unlike any other. Through art, we can engage in a loving correspondence with the soul of the world and model what I think of as “deep seeing,” the kind of seeing that obliterates the boundaries between “us” and “them” so we can engage in literary advocacy that contributes to the betterment of the world.

We measure what we do against ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision of what he calls “the useful arts of civilization.” To be sure, that phrase has many meanings, but I have come to understand it as referring to what I call “the living arts,” meaning arts that are deeply embedded in the community — embedded but distinct from the kind of collective art experiences that so often emerge in the context of, say, a Ruhi study circle. No, we are not all artists any more than we are all brain surgeons or physicists. Mastery of an art requires a steady practice, years of skill building, an understanding of technique, and the development of an original voice and vision. “The people of Bahá,” Bahá’u’lláh tells us, “should treat craftsmen with deference...” (Tarázát). It takes years of study, practice, and prayerful devotion to become someone who can call themselves a craftsperson — an artist. At e*lix*ir, we feel this must be acknowledged.

In our ten years at e*lix*ir, we have taken steps towards forging a new aesthetic through experiments that, as I explain in “Joining the Circle: Art and Spirituality at Little Pond,” attempt to integrate prayer and meditation into the artistic process. Such experiments represent what I describe in that piece as “steps along a path towards a new aesthetic in which artistic practice might merge with spiritual practice.” So it is, too, I believe, with “Celestial Navigations,” a long poem shared in issue no. 3 that was the fruit of sustained reflection on Bahá’u’lláh’s Tablet of the Holy Mariner.

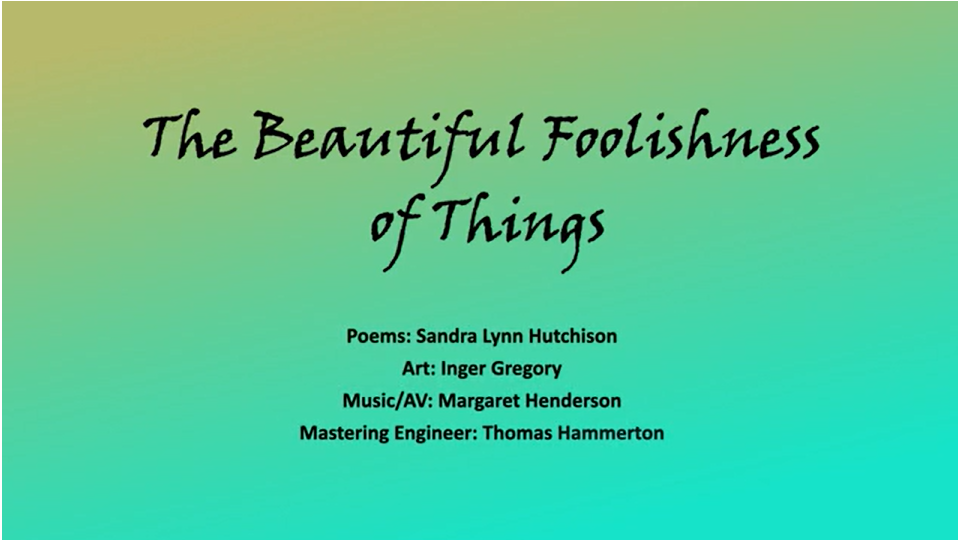

In the pages of e*lix*ir, we have, whenever possible, made space for collaboration between artists, especially between artists who work in different media. As I wrote in the editorial for issue no. 11, the kind of deep seeing we need now is not individual, but collective. We hope and believe that the collaborative work featured in e*lix*ir has charted a path artists might follow in future. One needs only to take a look at the following collaborations to get some idea of what might be possible: “The Beautiful Foolishness of Things,” which appears in this issue; “The Skies She Didn’t See;” “The e*lix*ir Poetry Collective Writes the Creation;” and the remarkable collaboration between visual artists Nikki Manitowabi and Pam Jackson in portraying their beloved green island. Noteworthy in this respect, too, is the exhilarating opportunity generated by Irish poet Anton Floyd, whose two books of poetry we reviewed in issue no. 14, for e*lix*ir poets to share their work along a poetry trail at the Kilkenny Arts Festival Fringe in the city of Kilkenny in West Cork, Ireland.

In an effort to clothe the body of art with a new garment, we, at e*lix*ir, have imagined new genres — forms of exaltation. Most notable of the forms of exaltation that emerge in the pages of e*lix*ir is, no doubt, the Personal Reflection Piece, which, as I described it in issue no. 8, is “[a] unique literary form that combines reflection and analysis with creative writing in a prose shaped by poetic elements” and “offers readers an opportunity to deepen their engagement with Bahá’í scripture not just as readers but as writers.”

Most of the personal reflections on the Bahá’í Writings published in e*lix*ir had their origins in a course I taught through the Wilmette Institute and now teach through The Corinne True Center for the Study of History and the Texts — “Writing about the Writings: The Art and Craft of the Personal Reflection Piece.” Among them are two of the reflection pieces we feature in this issue: A. Philip Christensen’s magnificent “The Mystery of Proximity and Remoteness” and James Andrews’ heartfelt and deeply pondered “Fire and Paradise.” We also feature one of my own past contributions to the form in this issue, “Our Verdant Isle,” in which I offer my reflections on Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of a maiden standing on a pillar of light.

At e*lix*ir, we have tried our best to stay in sync not with world events but with the Bahá’í calendar and pattern of life — with holy days and years, seasons of the spirit, and with unfolding events in the Bahá’í community. To this end, we have launched several special issues to mark signal events and to engage with concerns of importance to the community. We dedicated issue no. 4 to showcasing Bahá’í literature for children and issues no. 6 and no. 9 to marking the bicentenaries of the births of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb.

With respect to engagement with key events in the life of the Bahá’í community, the crowning event in the past decade at e*lix*ir was undoubtedly the Global Poetry Reading we feature in this issue. The online reading, which marked the centenary of the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, brought together nine poets from five countries and was attended by over one hundred people. All present agreed that it was an event in which art and worship, creative life and spiritual life were woven seamlessly together in a fabric of exquisite beauty.

Of grave concern to us throughout the past ten years has been the ongoing persecution of the Bahá’ís in Iran. To draw attention to this injustice, we devoted two issues, no. 9 and no.15, to stories written by Bahá’ís, mostly youth, who live in Iran. And in issue no. 17, we featured writing and art generated in response to the Our Story is One campaign, which was launched to commemorate the ten Bahá’í women executed in Shiraz in 1983 and to draw attention to the present-day struggles of women in Iran to achieve greater equality in their country.

What ‘Abdu’l-Bahá refers to as “this holy land of Persia” loomed large in the journal over the past ten years, becoming a focal point for our literary explorations and advocacy, in part because of my own involvement as a teacher in the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE). Most of the pieces that appear in the “Voices of Iran” section of the journal grew out of essays I assigned to the undergraduates in my writing courses, but these essays are so much more than undergraduate essays: what we have in them is nothing less than a precious piece of history. Indeed, the journal, in all its richness, would not be what it is without the voices of the students and faculty in the BIHE.

Before I highlight what were, for me, some of the most memorable of these essays, I want to draw attention to the comic that has appeared in most issues of the journal. When in the spring of 2018, I proposed a comic entitled Ruhi & Riaz to Eira, an undergraduate in one of my writing classes, she latched on to the idea and ran with it, creating what is one of the most beloved of our regular features. The installment featured in this issue was created by Eira, now a BIHE faculty member, in the wake of the Women, Life, Freedom Movement. It is telling that in this installment of the cartoon, Ruhi is no longer wearing a hijab and is sitting with Riaz on a hill overlooking the city of Tehran, talking with him about what they can do to bolster their spirits. Surely, this installment of Ruhi & Riaz tells us much about the emotional temperature of those difficult days.

I also would like to draw attention to an essay featured in this issue, one written by Kimiya Roohani, another young faculty member in the BIHE: “What Mona Wanted.” If you want to know more about the crises faced and victories won by the valiant faculty members in the BIHE, read this piece. It rings with vision and reverberates with a seemingly indomitable spirit of resilience. Another piece included in this issue, this one a letter written by the students in my journalism class at the height of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, gives voice to the aspirations of Bahá’í youth in Iran with respect to their fellow citizens. Read “Dreaming of a Better Iran” if you want to know what the Bahá’í youth in Iran want their fellow Iranians to understand.

As I mentioned in issue no. 16, when I imagine what art forms writers may use in future, I can’t help but think that the letter, that intimate form of communication employed so often in the Bahá’í Writings themselves, will continue to offer enormous scope for the expression of the deepest yearnings of the soul. Letters such as Andishe Taslimi’s “A Small Light in a Dark Room,” which we share in this issue, inscribe the hopes, dreams, and struggles of a generation. Featured in issue no. 17, Maava’s “A Letter to Mona from Shiraz” and Bahar Rohani’s “A Letter to Mona from Yazd” also provide insight into the complex feelings — inadequacy, awe, and soaring hope — Bahá’í youth in Iran may experience as they reflect on the past sacrifices of their fellow believers and confront their own uncertain future.

The “Voices of Iran” section of the journal featured several enthralling stories about pilgrimage. Nazanin Eslami’s “The Silence of Being Heard,” which appears in issue no. 13, tells the story of a covert pilgrimage made at night to the site in Shiraz where the Báb’s house once stood, while Rojin Ghavami’s “A Glimpse of the Glorious Landscape of Freedom” offers stirring reflections on a first trip outside Iran, to visit Bahá’u’lláh’s house in Edirne. And Mahsa Foroughian’s account in “The Court of Holiness” of her travels through the “desolate proud mountains” in the north of Iran to Takur, the village of Bahá’u’lláh’s birth, is forever engraved in my mind.

So many moving stories of crisis and victory from Iran fill the pages of e*lix*ir — it is difficult to choose the most outstanding ones. Each writer had a story to tell and did so in a voice fully authentic. For now I will simply draw your attention to the essays that took up the most space in the rooms of my own mind when I first read them and which have remained there, as permanent furniture: “Reading Anne Frank in Isfahan” by Sahba, a piece that was reprinted in Brilliant Star; “Knowing God through His Creation” by Nava Eslami, which was reprinted in bahaiteachings.org; and “Calamity: The Path to Eternity,” a reflection on Hidden Word Arabic No. 52 written by Hannan Hashemi just days before she was detained by Iranian authorities for a fabricated crime. And in this issue, we share another outstanding piece, which was reprinted in Brilliant Star: Sahba’s “Riding a Purple Bicycle in the City of Isfahan.”

I call to mind, too, “The Grief of War” by Tanin Azadi — a firsthand account of the Iran-Iraq war — and Saba Shadabi’s “A Weekend in a One Hundred Star Hotel,” a mesmerizing tale of her visit to an all-Bahá’í rose-growing village in rural Iran. Ali F’s moving account of his long journey “From Yazd to Tihran” for in-person classes has stayed with me, as has silenced Iranian opera singer Ellie’s heartrending audio recording of a well-known solo from the Broadway musical Les Misérables, “I Dreamed a Dream.”

I would like to mention, too, a delightful Persian-language children’s book, “The Painting,” as well as Sara Shakeri’s vividly accurate pencil sketch of the upper room of the house in Shiraz where the Báb declared His mission. And I would like to draw special attention to two powerful essays by Melika Rezvani: her account of a bittersweet wedding ceremony that took place in prison and her utterly heartbreaking account of the martyrdom of her father in “The All-Highest Paradise.” Finally, I would like to draw readers’ attention to an essay I revisit at regular intervals, an essay as profound as it is simple: “The Gate to Eternal Life” by Roxana Karamzadeh. If you ever find yourself in a place of forgetfulness, in which you feel your spirit has wandered off course, read this piece: it will remind you of everything you need to know about the true purpose of your life.

Poetry can constitute the most intimate form of loving correspondence — with others, with the world, with our own souls. In the course of collecting poetry from a diverse array of people and places over this past decade, I was struck by my discovery of these poets: Heather Hutchison for her remarkable truth telling about illness, Monte Schooley for his poignant evocation of the world of rural southern Ontario in the last century, and YoungIn Doe for her poignant accounts, in Korean and in English, of a life lived with great intensity.

I cannot end my remarks on poetry without highlighting the work of Lynn Ascrizzi and Christine Pratt, both of whom are no longer with us. I believe that the poetry of both Lynn and Christine is as good as any work being published in America today — probably better. Knowing this causes me to reflect on how much the work of the poet depends on promotion to be known and appreciated. May it not be so in future. It was only through a course I taught at the Wilmette Institute, “Gifts of the Spirit: The Spiritual Practice of Creative Writing,” that I was able to discover the work of Christine Pratt, Harriet Fishman, James Andrews, Arlette Manasseh, and others. My work with e*lix*ir has also made me aware of how many good Bahá’í poets are being published and read: for example, Imelda Maguire, Anthony A. Lee, Anton Floyd, Ruth Forman, and Andréana Lefton.

While I did not, during these ten years, come across many works of fiction I felt compelled to publish, I did find myself delighted and, quite frankly, surprised, by what I did find. Ivory and Paper, the coming-of-age fantasy novel by Ray Hudson, an excerpt from which we feature in the fiction section of this issue, is, to my knowledge, the first novel to be rooted in Unangan culture, history, and folklore. Set in the Aleutian Islands, where Hudson made his home for three decades, Ivory and Paper was published by the University of Alaska Press not long after we shared an excerpt from it in issue No. 5. Another piece of fiction, Tanin’s “The Bluest Part of the Sky,” which is also featured in this issue, tells the powerful and heartrending story of an imagined execution — of a family member. I was dumbfounded when I considered how the familiar maxim “write what you know” applied to this work of fiction. This may be one of the first pieces of fiction written by a Bahá’í on this theme, but, given the Iranian government’s cruel treatment of the Bahá’ís, it will probably not be the last.

In the special issue we devoted to our community’s “most precious treasure,” our children, we featured a number of wonderful storytellers and artists who have dedicated themselves to producing high-quality Bahá’í-themed literature for children: Ronald Tomanio, Patti Rae Tomarelli, Beverlee Patton, Jeannie Hunt, and Leona Hosack. And I cannot say how pleased I was to be able to share in that issue an excerpt from Basir Samimi’s Children of Destiny, a fantasy novel nominated for one of Iran’s most prestigious awards for fiction: the 2016 Afsaneha Award for Best Fantasy Novel. It is with a heavy heart I tell you that Basir Samimi, along with thirteen others, many youth, were, in 2022, sentenced to a combined total of 31 years in prison, simply for gathering together in a private home in the city of Qaemshahr in Mazandaran Province to discuss the role of education in social progress, an activity Iran’s Revolutionary Court erroneously described as engaging in “educational activities and propaganda at variance and against Islamic Sharia law.” The sentence was, eventually, reduced to a fine, but what a tragedy that a talented young writer such as Basir should find himself confined to a prison cell for a fictional crime.

We published some remarkable essays and memoir pieces in these ten years as well, none more worthy of note than the one we share in this issue: Elizabeth M. Green’s account in “An Invisible Wave” of witnessing a sit-in at a Woolworth’s counter in Jackson, Mississippi in the earliest days of the Civil Rights Movement and her subsequent journey to unpack white privilege in her own life. Also notable was a memoir published in issue no. 13, “The Fountain and the Thirsty One,” in which Mahvash Sabet offered a gripping account of how she found her poetic voice in prison.

I hope that my own essay “In the Noble Sacred Place: One Rainy Day in a Holy City” has served to bring those who have not yet explored Islam closer to that remarkable faith, as I hope my account in “A Landscape Yearning Towards the Light: A Year with the Paintings of Catharine McAvity” of the tests and difficulties that often follow illness or profound loss has encouraged artists to consider the ways in which such trials might serve to utterly transform their artistic practice.

In his essay, “Margaret Danner, the Black Arts Movement, and the Bahá’í Faith,” which we share in this issue, and in “The Literary Life of Rosey Pool,” Richard Hollinger has given us accounts of two literary figures of importance both to the Bahá’í community and the Black Arts Movement.

In the pages of e*lix*ir, we have also published what we believe to be two important retrospectives: one on several decades of the Bahá’í children’s magazine, Brilliant Star, which we share in this issue, and another on two decades of the Spirit of Children.

Since its first appearance in issue no. 2, we have tried, as often as we could, to include our “Writing Life” column in the pages of e*lix*ir. In this issue, we share one of the most notable installments of the column, written by Anthony A. Lee on translating Rumi’s poetry. Two other noteworthy pieces I would like to mention are “Notes on the Poetic Process,” which we also share in this issue, by the well-established Shenandoah Valley poet Michael Fitzgerald and “Trust in Poetry” by former Montana State Poet Laureate Tami Haaland.

In addition to these columns, we have published various craft-focused essays on well-known poets such as Jane Kenyon; Alicia Ostriker, whom I met at an all-night Sufi poetry reading in the Galilee; and Stanley Kunitz, whom I had the pleasure of hearing read at the launching of his final book at a bookstore in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village.

The art of translation has had a strong presence in e*lix*ir during these past ten years, with Tahirih’s well-known poem “If I Should Gaze Upon Your Face” being doubly translated, first from Persian into English by Shahin Mowzoon and myself and again from English into Chinese by Zijing Pan DiCenzo. Shahin Mowzoon and I also had a chance to share some of our translations of Mahvash Sabet’s poetry in the lead-up to George Ronald’s publication of our translation of her second volume of prison poems, A Tale of Love. Finally, I should say that I was delighted that two award-winning translators of Rumi, Anthony A. Lee and Nesreen Akhtarkhavari, were able, in issue no. 8, to offer us a translation of one of Rumi’s love poems, “I Tremble.”

I am delighted to recall that some of the translations published in e*lix*ir were of scriptural texts. In issue no. 9, a special bicentenary issue devoted to reflecting on Bahá’u’lláh’s pen, a translation by Nader Saeidi and Anthony A. Lee of “O Nightingales,” an ode by Bahá’u’lláh, was featured. Several other translations of scriptural texts appeared in that issue, including Saiedi’s rendering of a tablet addressed to Ali and Stephen Lambden’s translations from the Arabic of some devotional Writings by Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as well as his translation of Bahá’u’lláh’s “Tablet of the Sun of Reality.” In the same issue, we were pleased to share a commentary by Todd Lawson entitled “Signs: Quranic Themes in the Writings of the Báb” and Brian Miller’s essay, “The Art of Translation” in which he draws on the wisdom gained from a lifetime of translating Arabic texts into English, in particular his own rich experience in translating “Ode of the Dove.”

Some memorable and important interviews have appeared in our pages over the past ten years — most notably an interview we feature in this issue by Mehrsa Mastoori who met with Shahriar Cyrus, a painter living in Iran, to speak with him about his well-known painting, “The Twenty-Fifth of December 1981,” a striking portrait of seven of the then soon-to-be martyred members of the Yaran as they sat in a courtroom in Shiraz awaiting their sentence in what was clearly a mock trial, a travesty of justice. In various issues of the journal, we have published other outstanding interviews with artists, such as the one in issue no. 16 with painter Hooper Dunbar and in issue no. 1 with poet Mahvash Sabet. And although he may not be a well-known artist at this time, I cannot forget the interview in which Mehrsa Mastoori speaks with Erfan Hosseini, a santur player from Iran who swept listeners away with his stirring arrangement, for santur and voice, of the traditional Persian poem “Dard-e Eshgh.”

In addition to featuring Shahriar Cyrus’ painting, we were thrilled to be able to showcase, in issue no. 5, the work of Tlingit painter, carver, and printmaker Jim Schoppert — one of the most innovative Alaska Native artists of the twentieth century. Born in 1947 in Juneau, he worked at the intersection of Alaska Native and Euro-American art, tradition, and innovation. We share Schoppert’s work again in this issue. And before I finish speaking about the art we have featured in the pages of e*lix*ir, I would like to make special mention of the elegant calligraphy by Dr. Muhammad Afnan and Burhan Zahra’i, which we published in issues no. 6 and no. 3 respectively. No Bahá’í journal of the arts would be complete without offerings of this exquisite art.

We will let the work of the other artists we have featured in e*lix*ir speak for itself, but I did want to draw attention to the textile art of three women whose work appears in our pages: Helen Butler, Beth Yazhari, and Lynn Miller. As I mentioned in issue no. 11, the work of reconfiguring, repurposing, and reimagining has always been women’s work; and in the very tactile creations of these three women artists, such work rises to the level of worship. I was not surprised when Beth Yazhari’s “Day Star” called out to me to be the work featured on the cover page of the current issue, for it embodies so much of what we, at e*lix*ir, believe art should be: intimate, visionary — a pure emanation of that delicious fragrance in which our globe has been enwrapped since Bahá’u’lláh released His potent, musk-laden words into the world.

During these past ten years, we at e*lix*ir have taken care not to overlook the dramatic arts. In this issue, we share, once again, the first act of a play which appeared in issue no. 17, about a Bahá’í student in Iran who, even as she is working with classmates to produce a play about the ten Baha'i women who were executed in Shiraz in 1983, is herself detained by the authorities. And in an interview that appeared in issue no. 12, Anne Perry, creator of Luminous Journey and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in France, offered her insights into the art of filmmaking.

In our “Looking Back on Books” section, we have reviewed a host of books about which we wanted our readers to know, from the work of the celebrated Rumi scholar Frank Lewis in Rumi: Swallowing the Sun to that of Amin Banani, Jascha Kessler, and Anthony A. Lee in Tahirih: A Portrait in Poetry, Selected Poems of Qurrat’ul-‘Ayn. We have also drawn attention to important new publications such as the selection of the Bahá’í Writings published in Days of Remembrance. In the course of my own reviewing, I was thrilled to discover two very high-quality works of literary nonfiction: Bradford Miller’s Soul of the Maine House and Ray Hudson’s Moments Rightly Placed.

In speaking about e*lix*ir book reviews, we must be sure to offer copious thanks to Allison Grover Khoury for her seemingly endless stream of excellent reviews of Bahá’í-themed books for children, which were featured in the special column we created for her, “State of the Art.”

We must also thank our faithful collaborators Bev Rennie and Ann Sheppard for the stunning photographs that so often adorned our pages and Dean Wilkey for his moving photo narrative in issue no. 6 of places associated with the life of Bahá’u’lláh in the holy land. We thank, too, Shahin Mowzoon for serving as our staff translator. It was he who translated the text of “The Painting” for English readers and the prayer for children that appeared in the same issue, issue no. 4.

I want to express my gratitude to my daughter, Shira Hollinger-Levitsky, for conceiving the journal’s brand—e*lix*ir, styled with a lowercase “e” and two asterisks. It was just right then and it is just right now. It remains the signature of the journal. And I cannot finish without thanking my husband Richard Hollinger, an editor in his own right, for his unflagging support for e*lix*ir. He read every piece I wrote for the journal and looked over every section of every issue of the journal before it was published. His book, Agnes Parson’s Diary, a primary source which is of great importance to our understanding of the evolution of race issues in the Bahá’í community in America, was reviewed in issue no. 13 of the journal.

As I come to the end of this very long editorial, I find it difficult to summon the right words to show my appreciation for my indefatigable, visionary, and also very sensible co-editor, Michael “J.M.” Kafes, who came to me with considerable experience as an editor as a result of his work on a book of his own: In the Eyes of His Beloved Servants. It has been a decade of joyous and fruitful collaboration with JM, as he is called by his friends, as we shared a project we both loved.

As we round out ten years of e*lix*ir, I call to mind, once again, the words of Bahá’u’lláh: “Arts, crafts and sciences uplift the world of being, and are conducive to its exaltation” (Epistle to the Son of the Wolf). We hope that e*lix*ir has and will continue to uplift the world of being as we bring imagination, a spirit of praise, a deep connection to place, and a vision of the oneness of the human race together to create a potent elixir, one with the power to transform the most ordinary experiences into extraordinary art.

As I have written in the pages of this journal and as I continue to believe: the very best literary art comes into being when a lofty vision of the human enterprise and highly refined literary skills intersect with “life” as we know it, live it, and experience it in the present moment, with all its joys and sorrows. Let us continue, then, in all our joys and sorrows, to celebrate the elixir that is art.

— Sandra Lynn Hutchison